Scuba Diving on Rebreather in Grand Cayman Island

Everything has changed. With a single anxious breath, nearly a decade of carefully cultivated muscle memory is dashed, replaced by an entirely new perspective on diving. Seconds before, a reflexive, shallow draw on the mouthpiece should have delivered a blast of cold, compressed air — instead, nothing. Fighting a panicked urge to bolt for the surface, I paused to collect myself, and remembered the words of my instructor: “Pull hard, and trust the unit.” On the second, more-forceful attempt, I hear the regulator fire behind my right ear, and a flow of warm, moist gas satisfies my lungs’ hunger for oxygen. As the breathing loop fills to match the natural capacity of my lungs, I take a moment to acclimate as my heart rate slows. That’s when I begin to appreciate one of the biggest benefits a rebreather brings to diving: quiet. The other important advantages of closed-circuit systems will be revealed during this first checkout dive of my KISS Spirit LTE mCCR certification course. Four feet below the surface on a sunny Grand Cayman sand flat, I’m learning that mastering the KISS requires an open mind and faith in physics.

I used to envy rebreather divers. Not only did their gear look exponentially more badass than mine, they also were conspicuously absent during surface intervals, climbing back on board about when the rest of us had finished our second tank. From these strangers I learned the benefits: a blissful lack of bubbles, mind-expanding bottom times and a nearly endless supply of warm, moist air. Yet there were always reasons that kept me from converting — too expensive, too complicated, too risky. As the technology evolved and a new breed of recreational rebreathers emerged, my opinion began to shift. Try-out dives in pools at DEMA and PADI demonstration events continued to tip the scale. When the opportunity arose to get certified on a KISS CCR during an annual gathering of closed-circuit enthusiasts and photographers called Focus, at Grand Cayman’s Cobalt Coast Resort, I didn’t hesitate. I knew that on-site operator Divetech has catered to rebreather divers for years, and that many of its staff are vocal devotees. Plus, the island’s walls offer optimal conditions for this type of diving. It seemed like the perfect immersive training mission.

My instructor, Doug Ebersole, a cardiologist and CCR evangelist from Lakeland, Florida, greets me with a warm handshake and a cryptic message: “Your life’s about to change.” During the next three days I’ll master assembly, cleaning, testing and troubleshooting of the unit on dry land. Class sessions will help me understand the physiology of rebreather diving, along with the advanced nitrox theory required to operate one. Then we’ll make six dives, for a minimum of 500 minutes underwater, during which I’ll perform the skills needed to handle any emergency situation that might occur. (That’s right, six dives for 500 minutes — do the math.)

After a thorough tour, I discover it’s far less complicated than I expected — but a great deal more involved than screwing on a first stage. From a pile of parts, it takes me about 10 minutes to assemble, with a very necessary checklist but no tools. Designed with simplicity in mind, the unit uses mechanical components rather than electronic controls to deliver oxygen to the breathing loop. A hard-wired dive computer monitors all data, including depth, bottom time and the all-important PO2 level. With a simple one-button, manual-add valve, the diver squirts oxygen into the loop to maintain the proper PO2 level. In case of any electronic or mechanical failure, the diver needs to flip only a single lever to switch to a traditional open-circuit bailout system of air, and end the dive. It’s a simple safety net for a complex machine.

Hitting the water, the learning curve goes vertical. With an aluminum 80-cubic-inch bottle of air slung to my left side and the double-hose breathing loop draped around my neck, I ease off the dock at Cobalt Coast. This first dive will be shallow, with a 30-foot limit. The most difficult transition is relearning buoyancy control. The open-circuit method — inhaling and exhaling to make minor adjustments — is impossible with the constant volume of gas used by the rebreather. I bounce of the sandy bottom again and again for about 15 minutes before I acclimate and level of. Overcoming years of muscle memory — honed to achieve perfect trim — and becoming a poor-buoyancy poster child is beyond frustrating. But once the transition is achieved, it’s a different world underwater. The only sounds are my own regular breathing and the inhabitants of the reef, which have never been so loud. Under the careful watch of Ebersole — who stops me occasionally to test my emergency problem-solving skills (what to do in case of equipment failure, when to activate the bail-out valve) — I glide euphorically for nearly two hours, with checking my PO2 levels at regular intervals my only task-load.

Over the next three days, we’ll drop on signature Grand Cayman sites, such as Black Forest, Lemon Wall, Big Tunnels and Lighthouse Point. I have dived these sites before, but the CCR offers a more intimate experience because of the extended bottom times, which often reach past two hours — even after descending to 130 feet. Enjoying more time to explore the reef without the pressure of conserving air a la open circuit is downright blissful. And everything you’ve heard about up-close animal encounters is true. At Black Forest, a sleek Caribbean reef shark doesn’t speed away at first sight of our group of 10 — instead it hangs around, cruising a half-dozen lazy laps between divers.

On our final splash at Lighthouse Point, I interrupt a big green sea turtle gnawing on a sponge. It looks up, barely 3 feet from my face, and meets my gaze. I’m so close that I can count the wrinkles around its big, black eye. The stare-down lasts for minutes before the creature casually goes back to its lunch, unconcerned by my presence. In this moment I realize I am forever ruined for open-circuit diving.

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

Operator

A few dozen fin kicks from Grand Cayman’s famous North Wall, Divetech (divetech.com) offers complete services to CCR pilots, from absorbant to oxygen-friendly profiles, instruction, rentals, and expertise covering many different models.

When to Go

Diving is good year-round, but savvy divers visit during spring for prime weather, and from June to October for the best visibility.

Dive Conditions

Water temps average in the mid-80s in summer and high 70s in winter. Visibility regularly stretches past 100 feet.

Price

Focus Underwater (focusgrandcayman.com) includes lodging, meals, six days of boat diving and unlimited shore diving, photo seminars, photo competition, unlimited absorbant and gas fills, and more. A typical rebreather certification course runs about $1,500.

For Rebreather Options

kissrebreathers.com, hollis.com, diverite.com

ADVANTAGES OF OWNING A REBREATHER

1. The Ultimate Mix

The unit constantly monitors levels of oxygen and nitrogen in the breathing loop to create the safest balance and optimal PO2 based on depth.

2. Take Your Time

Because divers are breathing an optimized gas mix, the body absorbs far less nitrogen, allowing for dives longer than two hours at recreational depths. (Safety stops still apply.)

3. Easy Breathing

Gas that is warmed and moistened by the lungs is recycled through the loop, unlike on open circuit, where divers inhale cold, dry gas with each breath, which increases fatigue.

4. Silent Running

Without the ruckus of bubbles to frighten of marine life, your chances for life-altering close encounters with typically skittish creatures are greatly increased. (Did you read that, photographers?)

DISADVANTAGES OF OWNING A REBREATHER

1. Read the Manual

These are complicated machines that require careful assembly, mindful monitoring, disciplined maintenance and MacGyver-like troubleshooting skills. Lazy divers need not apply.

2. Unwelcome Mat

Finding dive operators that can supply absorbant and pure oxygen can be difficult in remote locations. And not all boat captains will allow rebreather-friendly profiles.

3. Ghost in the Machine

Because the unit relies on oxygen sensors and other electronics to function safely (redundancies aside), the chance for system failure is greater than with mechanical open-circuit diving.

4. One Size Doesn’t Fit All

Although based on the same principles, every rebreather is not the same, so there’s a different and specific training and certification for each model.

5. Deep Pockets Required

With most units ringing up for between $1,500 and $4,000, the price of entry is not cheap, not to mention the price of absorbant and oxygen.

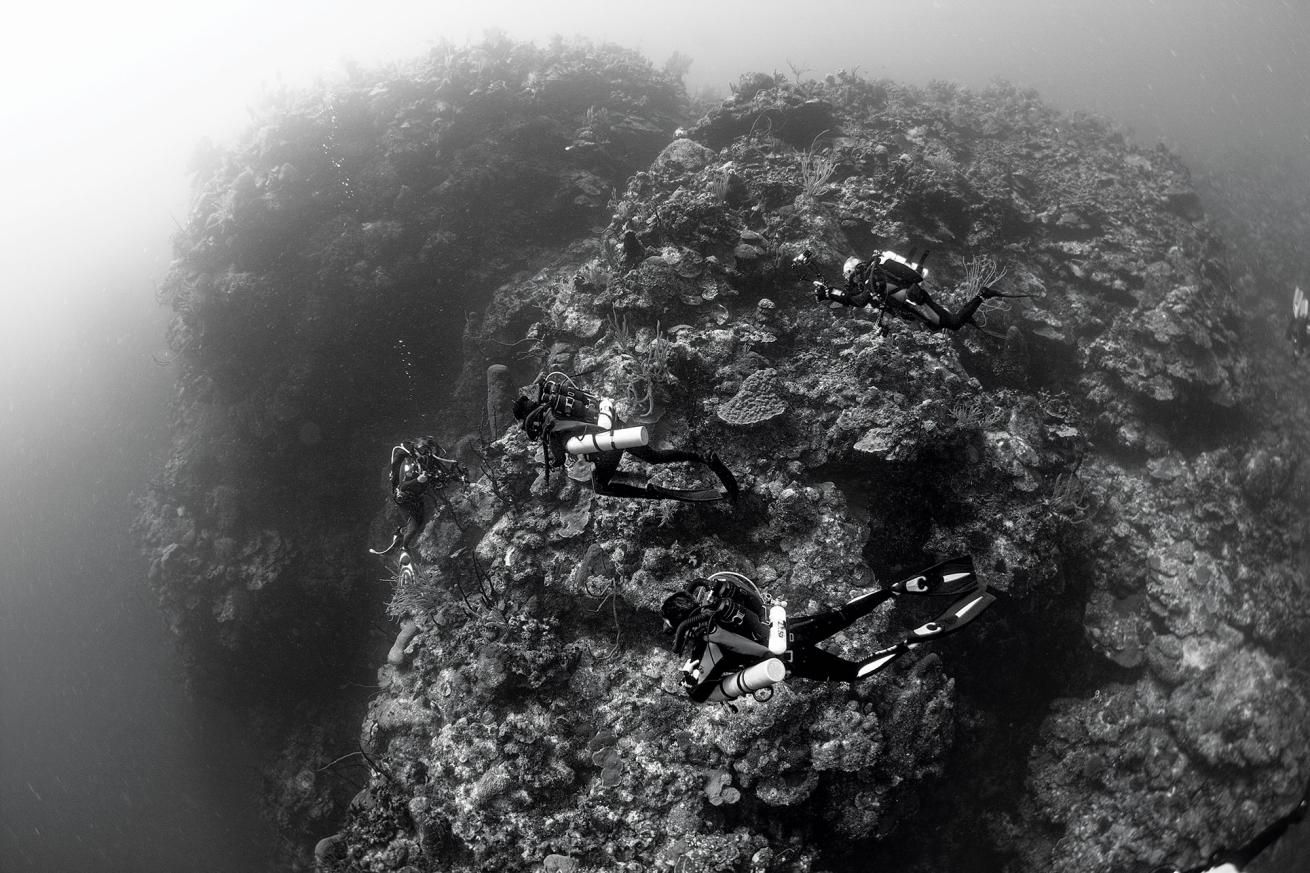

Tanya G. BurnettExploring inner space: CCR divers at the edge of Eagle Ray Pass, a deep reef on Grand Cayman.

Everything has changed. With a single anxious breath, nearly a decade of carefully cultivated muscle memory is dashed, replaced by an entirely new perspective on diving. Seconds before, a reflexive, shallow draw on the mouthpiece should have delivered a blast of cold, compressed air — instead, nothing. Fighting a panicked urge to bolt for the surface, I paused to collect myself, and remembered the words of my instructor: “Pull hard, and trust the unit.” On the second, more-forceful attempt, I hear the regulator fire behind my right ear, and a flow of warm, moist gas satisfies my lungs’ hunger for oxygen. As the breathing loop fills to match the natural capacity of my lungs, I take a moment to acclimate as my heart rate slows. That’s when I begin to appreciate one of the biggest benefits a rebreather brings to diving: quiet. The other important advantages of closed-circuit systems will be revealed during this first checkout dive of my KISS Spirit LTE mCCR certification course. Four feet below the surface on a sunny Grand Cayman sand flat, I’m learning that mastering the KISS requires an open mind and faith in physics.

Tanya BurnettA CCR diver explores the Kittiwake shipwreck in Grand Cayman.

I used to envy rebreather divers. Not only did their gear look exponentially more badass than mine, they also were conspicuously absent during surface intervals, climbing back on board about when the rest of us had finished our second tank. From these strangers I learned the benefits: a blissful lack of bubbles, mind-expanding bottom times and a nearly endless supply of warm, moist air. Yet there were always reasons that kept me from converting — too expensive, too complicated, too risky. As the technology evolved and a new breed of recreational rebreathers emerged, my opinion began to shift. Try-out dives in pools at DEMA and PADI demonstration events continued to tip the scale. When the opportunity arose to get certified on a KISS CCR during an annual gathering of closed-circuit enthusiasts and photographers called Focus, at Grand Cayman’s Cobalt Coast Resort, I didn’t hesitate. I knew that on-site operator Divetech has catered to rebreather divers for years, and that many of its staff are vocal devotees. Plus, the island’s walls offer optimal conditions for this type of diving. It seemed like the perfect immersive training mission.

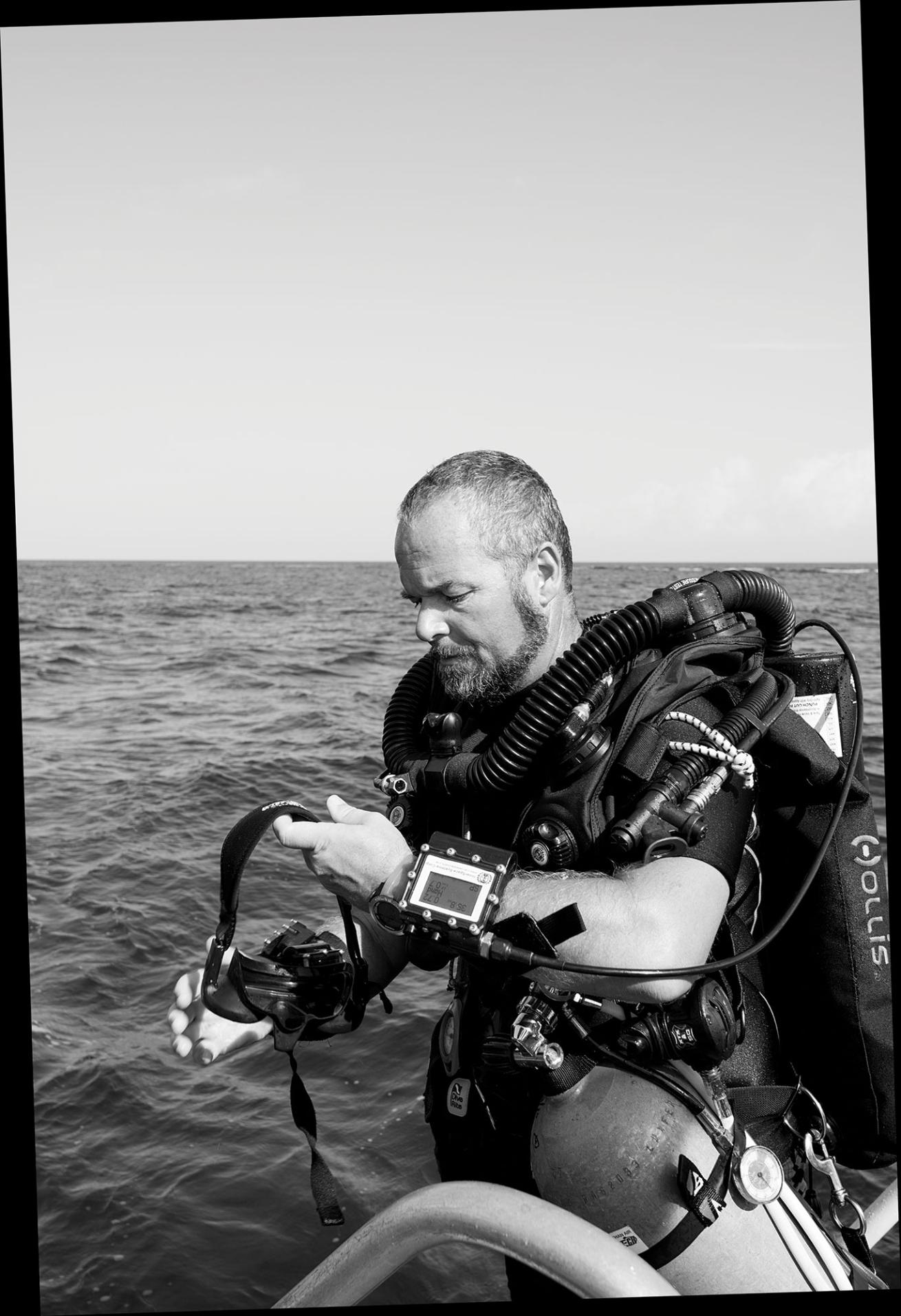

Tanya BurnettDoug Ebersole from Lakeland, Florida, was the author's instructor during his KISS rebreather certification.

My instructor, Doug Ebersole, a cardiologist and CCR evangelist from Lakeland, Florida, greets me with a warm handshake and a cryptic message: “Your life’s about to change.” During the next three days I’ll master assembly, cleaning, testing and troubleshooting of the unit on dry land. Class sessions will help me understand the physiology of rebreather diving, along with the advanced nitrox theory required to operate one. Then we’ll make six dives, for a minimum of 500 minutes underwater, during which I’ll perform the skills needed to handle any emergency situation that might occur. (That’s right, six dives for 500 minutes — do the math.)

Tanya BurnettGrand Cayman dive operator Divetech caters to rebreather divers.

After a thorough tour, I discover it’s far less complicated than I expected — but a great deal more involved than screwing on a first stage. From a pile of parts, it takes me about 10 minutes to assemble, with a very necessary checklist but no tools. Designed with simplicity in mind, the unit uses mechanical components rather than electronic controls to deliver oxygen to the breathing loop. A hard-wired dive computer monitors all data, including depth, bottom time and the all-important PO2 level. With a simple one-button, manual-add valve, the diver squirts oxygen into the loop to maintain the proper PO2 level. In case of any electronic or mechanical failure, the diver needs to flip only a single lever to switch to a traditional open-circuit bailout system of air, and end the dive. It’s a simple safety net for a complex machine.

Tanya G. BurnettThe wrecks and walls in Grand Cayman are perfect for CCR diving.

Hitting the water, the learning curve goes vertical. With an aluminum 80-cubic-inch bottle of air slung to my left side and the double-hose breathing loop draped around my neck, I ease off the dock at Cobalt Coast. This first dive will be shallow, with a 30-foot limit. The most difficult transition is relearning buoyancy control. The open-circuit method — inhaling and exhaling to make minor adjustments — is impossible with the constant volume of gas used by the rebreather. I bounce of the sandy bottom again and again for about 15 minutes before I acclimate and level of. Overcoming years of muscle memory — honed to achieve perfect trim — and becoming a poor-buoyancy poster child is beyond frustrating. But once the transition is achieved, it’s a different world underwater. The only sounds are my own regular breathing and the inhabitants of the reef, which have never been so loud. Under the careful watch of Ebersole — who stops me occasionally to test my emergency problem-solving skills (what to do in case of equipment failure, when to activate the bail-out valve) — I glide euphorically for nearly two hours, with checking my PO2 levels at regular intervals my only task-load.

Over the next three days, we’ll drop on signature Grand Cayman sites, such as Black Forest, Lemon Wall, Big Tunnels and Lighthouse Point. I have dived these sites before, but the CCR offers a more intimate experience because of the extended bottom times, which often reach past two hours — even after descending to 130 feet. Enjoying more time to explore the reef without the pressure of conserving air a la open circuit is downright blissful. And everything you’ve heard about up-close animal encounters is true. At Black Forest, a sleek Caribbean reef shark doesn’t speed away at first sight of our group of 10 — instead it hangs around, cruising a half-dozen lazy laps between divers.

Tanya BurnettWhat's missing? Bubbles. CCR diving lets you get up close and personal with wildlife in a new way.

On our final splash at Lighthouse Point, I interrupt a big green sea turtle gnawing on a sponge. It looks up, barely 3 feet from my face, and meets my gaze. I’m so close that I can count the wrinkles around its big, black eye. The stare-down lasts for minutes before the creature casually goes back to its lunch, unconcerned by my presence. In this moment I realize I am forever ruined for open-circuit diving.

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

Operator

A few dozen fin kicks from Grand Cayman’s famous North Wall, Divetech (divetech.com) offers complete services to CCR pilots, from absorbant to oxygen-friendly profiles, instruction, rentals, and expertise covering many different models.

When to Go

Diving is good year-round, but savvy divers visit during spring for prime weather, and from June to October for the best visibility.

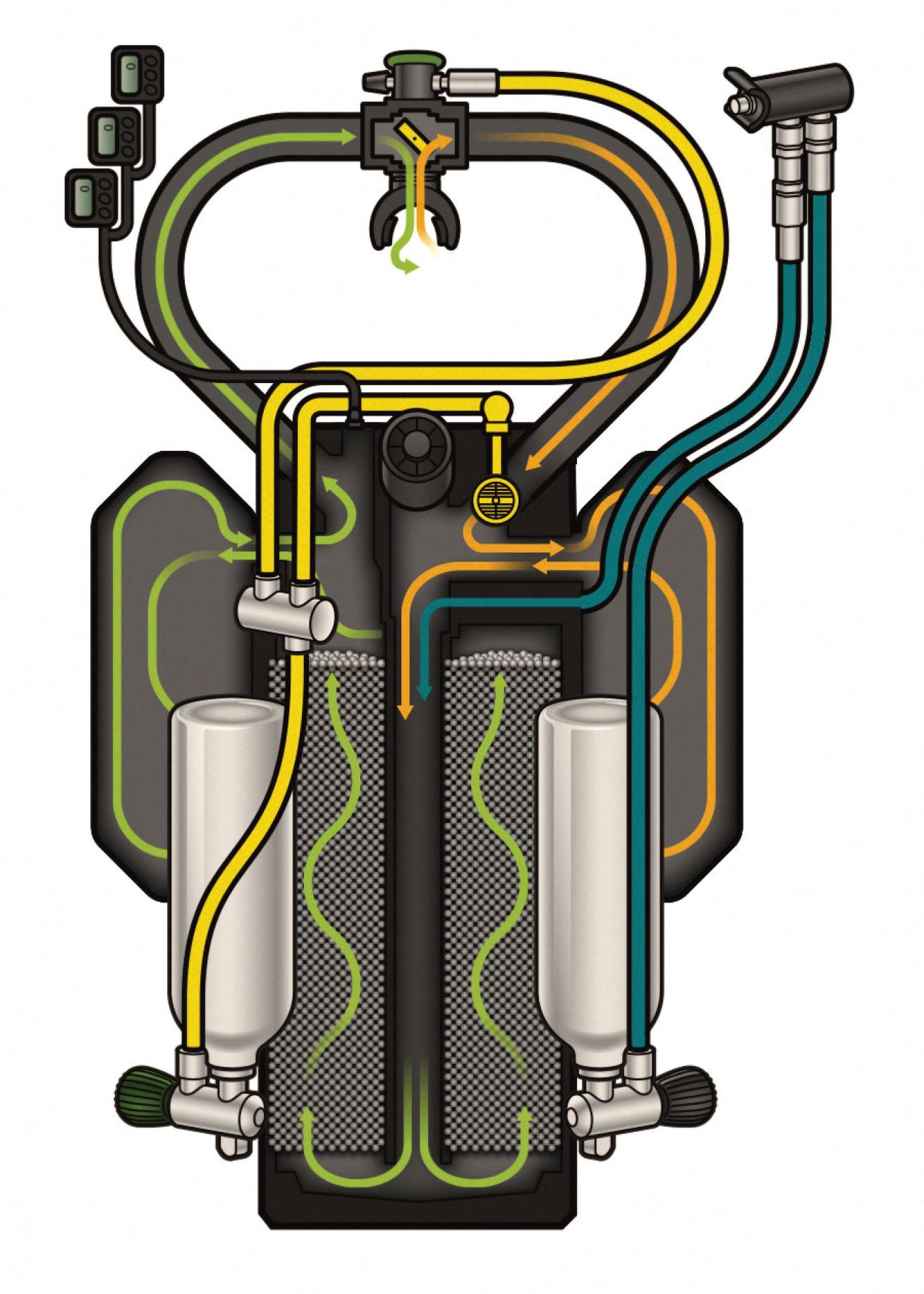

James ProvostHow a Rebreather Works Rebreathers are built around a one-way breathing loop (we’ve illustrated a Classic KISS). All rebreathers — oxygen, semi-closed circuit and closed circuit — “scrub” exhaled carbon dioxide. One hose takes the exhaled breath to the CO2 scrubber, and another brings it back (without the CO2). After that, how the rebreather works depends on the specific rig, but generally, a counterlung expands and contracts to accommodate your breathing. A relief valve vents excess gas and the input valve adds more oxygen, nitrox or trimix. The exhaust and input valve can be attached to the actual lung or on the scrubber head. The rebreather then replaces the oxygen you’ve breathed. A tank of pure oxygen or mixed gases injects fresh gas into the breathing loop. Sensors monitor the partial pressure of O2 in the breathing gas on all rebreathers. A computer system on electronic rigs adds and adjusts the gases; on mechanical rigs, the mechanics of the design brings more breathing gas into the loop. These types have a manual override, so the diver can easily add gas. (Electronic rebreathers have this option also.)

Dive Conditions

Water temps average in the mid-80s in summer and high 70s in winter. Visibility regularly stretches past 100 feet.

Price

Focus Underwater (focusgrandcayman.com) includes lodging, meals, six days of boat diving and unlimited shore diving, photo seminars, photo competition, unlimited absorbant and gas fills, and more. A typical rebreather certification course runs about $1,500.

For Rebreather Options

.Resolution: I will subscribe to Scuba Diving magazine. ;)

ADVANTAGES OF OWNING A REBREATHER

1. The Ultimate Mix

The unit constantly monitors levels of oxygen and nitrogen in the breathing loop to create the safest balance and optimal PO2 based on depth.

2. Take Your Time

Because divers are breathing an optimized gas mix, the body absorbs far less nitrogen, allowing for dives longer than two hours at recreational depths. (Safety stops still apply.)

3. Easy Breathing

Gas that is warmed and moistened by the lungs is recycled through the loop, unlike on open circuit, where divers inhale cold, dry gas with each breath, which increases fatigue.

4. Silent Running

Without the ruckus of bubbles to frighten of marine life, your chances for life-altering close encounters with typically skittish creatures are greatly increased. (Did you read that, photographers?)

DISADVANTAGES OF OWNING A REBREATHER

1. Read the Manual

These are complicated machines that require careful assembly, mindful monitoring, disciplined maintenance and MacGyver-like troubleshooting skills. Lazy divers need not apply.

2. Unwelcome Mat

Finding dive operators that can supply absorbant and pure oxygen can be difficult in remote locations. And not all boat captains will allow rebreather-friendly profiles.

3. Ghost in the Machine

Because the unit relies on oxygen sensors and other electronics to function safely (redundancies aside), the chance for system failure is greater than with mechanical open-circuit diving.

4. One Size Doesn’t Fit All

Although based on the same principles, every rebreather is not the same, so there’s a different and specific training and certification for each model.

5. Deep Pockets Required

With most units ringing up for between $1,500 and $4,000, the price of entry is not cheap, not to mention the price of absorbant and oxygen.