Advanced Diving: The Wreck of the Red Sea's Thistlegorm

It’s a little after daybreak. The quiet on board breaks without warning, replaced with loud commands delivered in terse Arabic as the agile crew swings into position to man the lines. We have arrived. My dive boat has been motoring along the coast of Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula for nearly four pre-daylight hours. I walk out of the main cabin, where I’ve slept most of the bumpy ride huddled on the thin cushions of the bench lining the wall, and see the divemaster disappear over the side, bounce diving to tie a guideline from our stern to the wreck. I pour a cup of thick Arabic coffee from the galley and groggily prep my gear in the early morning light. In a few minutes, I’ll hop off the stern myself and make my way to the seafloor to penetrate the deepest bowels of what is arguably the most famous and historically rich shipwreck in the Red Sea.

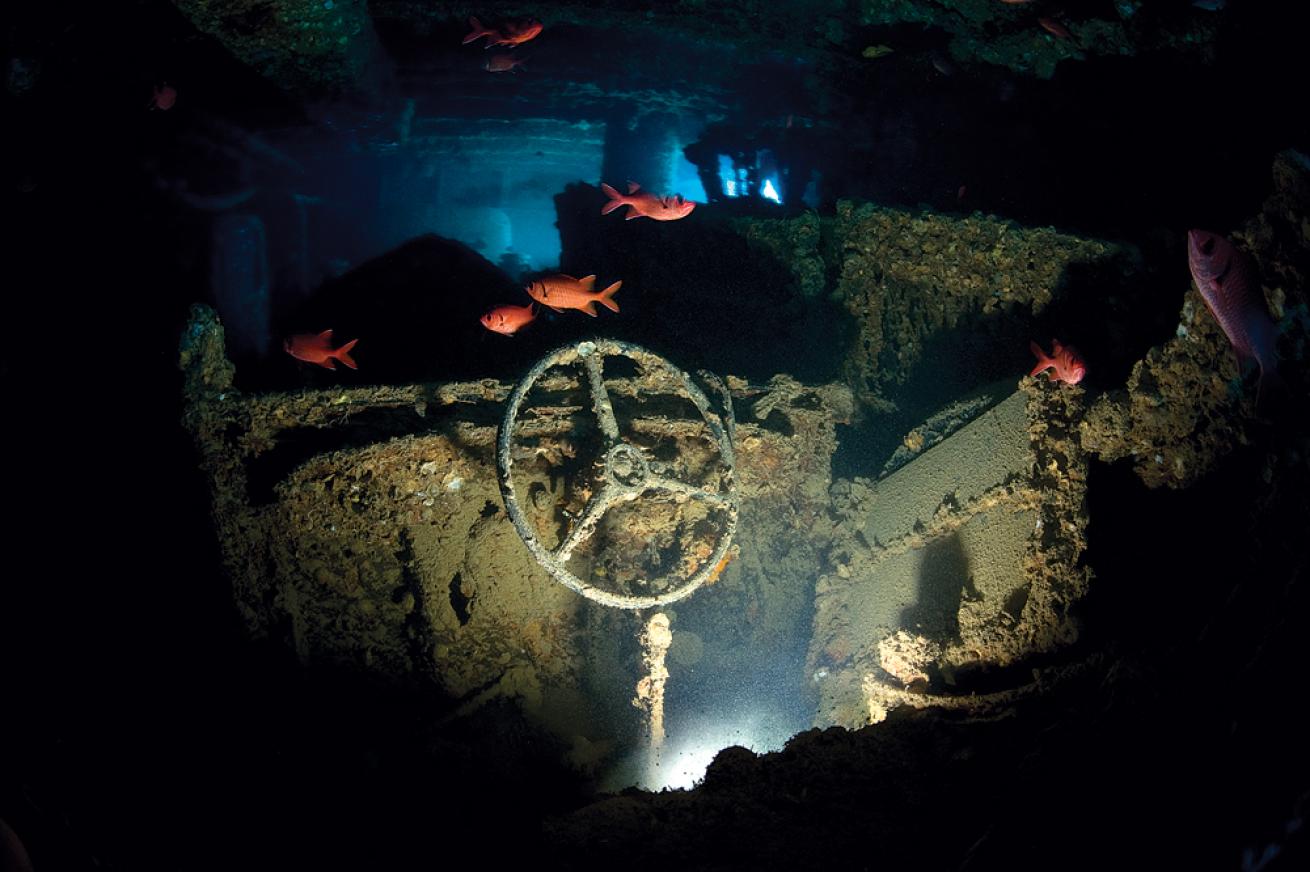

A dive trip to the British supply ship SS Thistlegorm requires no small amount of time and effort, but it’s unquestionably worth it for an opportunity to slip inside this veritable World War II time capsule, buried by a hailstorm of German bombs in 1941 while en route to deliver her cargo of supplies to Allied troops in Suez. After sinking, the Thistlegorm lay undisturbed for about 14 years, explains John Kean, an experienced Thistlegorm guide and author of the book “SS Thistlegorm: The True Story of the Red Sea’s Greatest Shipwreck.” At which time a budding explorer named Jacques Cousteau — piloting another soon-to-be-legendary ship, the Calypso — moored up to her and made the first-ever scuba-fueled explorations of her decks. Jump forward to today, and the Thistlegorm draws tens of thousands of divers every year. I make one final check of the surface conditions. Out here at the mouth of the Gulf of Suez, current and surface chop are common, and today has both. So I giant-stride off the stern with an empty BC and make a beeline down the guide rope to get into the protective shelter of the Thistlegorm’s hull. Descending over the blast zone — where German bombs detonated munitions holds near the stern — I can see both sections of the 415-foot-long ship: The front half sits mostly intact, upright at the shallower end of the sloping seafloor, while the stern, twisted 90 degrees, rests on its port side in about 95 feet of water. As I approach the jagged, torn opening in the hull, I glide over the tracks of a pair of Mark II Bren Carrier tanks, upside down in the pile of munitions, rubber boots and twisted metal. Unlike a passenger ship, with an interior full of winding passageways and cabins, the Thistlegorm features wide-open cargo holds and no shortage of vertical exit points. And slipping inside the wreck at Hold 3 feels a bit like walking into a war museum where shafts of sunlight illuminate the displays through skylights in the roof. Once my eyes adjust to the semidarkness, I find myself surrounded by piles of explosives — hand grenades and anti-tank mines — scattered in a state of disarray pretty much as they fell after the ship touched down on the seafloor. It’s an impressive collection, but I know the most striking is ahead of me in the forward compartments. The Thistlegorm’s first and second holds overflow with a payload of large war material, frozen in time. My gaze extends across row after row of Bedford trucks, intact down to the tires and packed in the belly of the ship like sardines. And each truck bed is loaded to capacity with BSA motorcycles. Packed into corners and stacked along walls sit crates of medical supplies, Enfield rifles standing straight up in their racks and endless boxes of ammunition. The gravity of this cargo hits me like a wave. It’s a mere drop in the bucket of what was required to keep that massive Allied war machine moving, but people’s lives depended on this stuff — they never got it, and good people died trying to deliver it. All to soon, my time runs short. I make my way shallower by traversing through the upper holds and spend a few brief moments exploring the rail cars, davits and a torpedo on the upper deck before finning to my guideline. My bottom time is maxed out, so I make a slow ascent and give myself an extra-long safety stop. When I climb back on board, the boat has fallen quiet once again. I can speak only for myself, but it seems like we all need a moment of quiet reflection to digest the experience. But before we can think too long, the cook swings up from the galley, cracking jokes through a smile as thick as his accent, passing around cups of heavily sugared tea and coffee and ushering us inside for a hearty meal before we move on to drift the walls of Ras Mohammed.

Dive 1 - Yellow Path

Start with a deep dive around the stern and then explore the exterior of the wreck. The stern section rests on its port side, which makes the huge propeller and rudder near the seafloor must-see features. Along your way around the back end, you’ll pass anti-aircraft guns before reaching the bombed out area. Spend a few minutes here exploring the debris field — a keen eye can spot a wide variety of loose artifacts. From here ascend to the shallower depths at the top of the superstructure. Make light penetrations into the captain’s cabin and bridge before swimming along the top deck, which still sports railcars, a torpedo, davits, masts and winches.

Dive 2 - Orange Path

The second dive is all about the interior. The best access point is Hold 3, just forward of the bomb damage — this lets you start at depth and work your way shallower as you move toward the bow. Holds 1 and 2 house Morris automobiles, BSA motorcycles, Bedford trucks, ammunition, Enfield rifles still loaded in their racks, as well as crates of medicine, tires and mounds of rubber “Wellington” boots. And be aware, the Thistlegorm is an extremely popular dive, and it’s common for two or three groups to be inside the wreck at any given time. So, bring a light and stay close to your guide when inside the wreck so you don’t mistakenly follow the wrong group of divers.

What it Takes: The wreck is in a remote location, the dives are deep, bottom times are long, and the bulk of the dive time is spent exploring the dark, cramped interior of the ship. An advanced certification and experience with all the above are a must. The following specialty courses are recommended: Wreck, Deep, Peak Performance Buoyancy. All areas of the ship are accessible to recreational divers, though technical training, such as advanced nitrox, decompression diving and a dual-tank setup will allow great depth of exploration on each dive.

Need to Know:

When to Go: The Red Sea’s desert coastline sees very little rain, and there’s almost no freshwater runoff, making for great visibility and diving conditions year round, but conditions do vary by season. Summer — May to October — brings water temps in the mid-80s, along with scorching topside weather; winter — November to April — boasts more-comfortable air temps, but the water can drop to 70 degrees or lower.

Liveaboard Operator: Red Sea Aggressor.

Alexander Mustard

Alexander Mustard

Alexander Mustard

Alexander MustardTruck aboard the Thistlegorm

Alexander Mustard

Alex MustardThis BSA M20 motorcycle in Hold 2 of the SS Thistlegorm was part of a shipment of military equipment on its way to aid the Allies during World War II.