Heart Disease and Diving: How To Make Long Term Lifestyle Changes

Courtesy Eric DouglasLessons for Life author Eric Douglas takes us through his cardiac rehab regimen and explains how he will return to scuba diving.

Chapter 3: Making Long-Term Changes

For the most part, people who have a heart attack, receive stents, or undergo open-heart surgery for coronary artery bypasses don’t make any changes to the lives after the event. That’s probably the most stunning thing I have learned since beginning rehab after my open-heart surgery. The staff at my hospital says it’s somewhere in the 75 percent range who don’t make any changes. They don’t attempt to improve their health, get more exercise, eat better or quit smoking. I am completely amazed by that.

After I published the first column in this series, I heard from a number of other divers who have already faced heart troubles and have successfully returned to diving. I’ve also heard from a couple of people who are just a week or two behind me in the process. One fellow diver asked me what cardiac rehab is, even though he had had his own heart issues. I was surprised he hadn’t been referred to a rehab program so I realized I should probably explain what it encompasses, just in case.

Read the Full Series Here

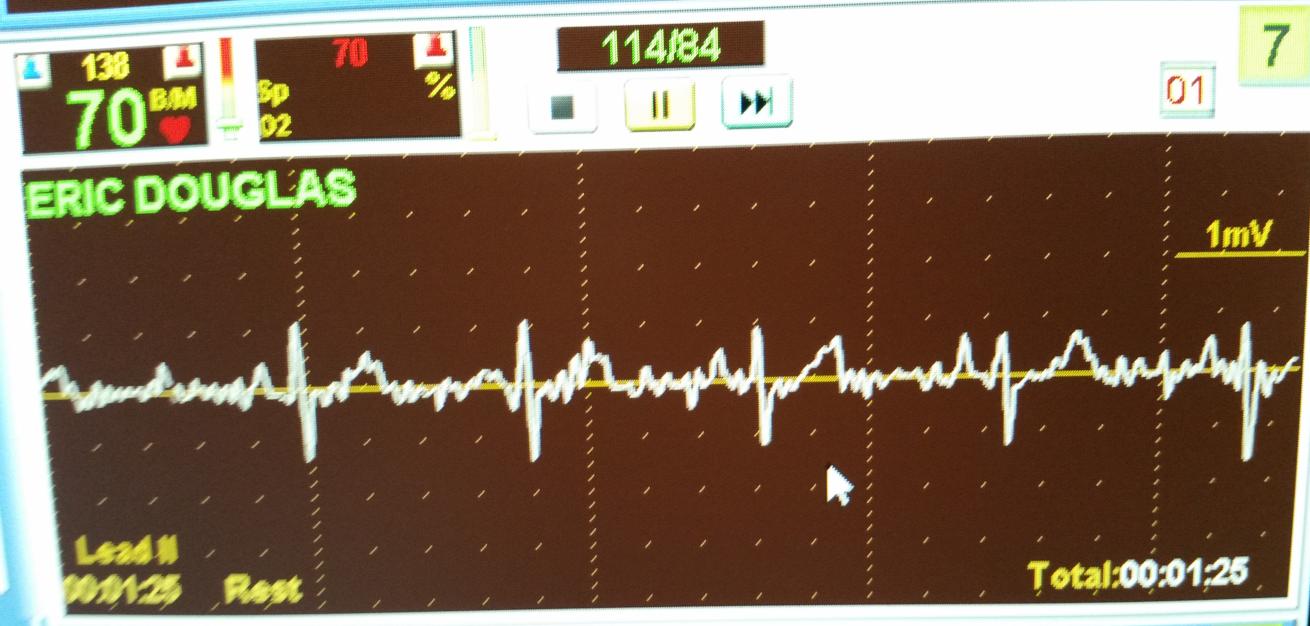

Courtesy Eric DouglasDuring cardiac rehab, patients are put on a three-lead heart monitor so the doctors can keep an eye on pulse rates and heart rhythms during exercise.

What is Cardiac Rehab?

Cardiac rehab is a supervised exercise program. In my case, it started about a month after surgery. I understand it typically starts four to six weeks after surgery, but it depends on the person and their overall fitness. It might take longer. I visit the hospital’s rehab center three days a week for 12 weeks where I exercise with others who are in a similar place in terms of heart-health. The staff checks our blood pressure, and we put on a three-lead heart monitor so they can keep an eye on our pulse rates and heart rhythms during exercise. All of the exercises they put us on are cardiovascular in nature. For me, it was rowing, riding a fan bike, walking on a treadmill and riding a recumbent bike. Others use stair climbers or step blocks.

I’m not diabetic, but they also check the blood sugar for anyone who is. At the end of the workout session, they recheck our blood pressure. This whole process serves an important purpose. We learn how to exercise, and push our limits, while knowing that someone is watching to make sure nothing is out of whack. My personal motto is that if they don’t tell me to slow down at least once during a workout, I’m not doing my job. I want to push myself under their care.

In the last installment I discussed the healthy dose of paranoia that comes as a result of heart surgery. You worry about every pain or niggle in your body. Exercising while supervised and monitored helps reduce those fears.

The other element of cardiac rehab is education. Honestly, when I began the process, I wasn’t sure I would learn all that much from this portion. I’ve exercised much of my adult life. I’ve also taught CPR and first aid classes at the instructor trainer level and been an EMT and a diver medic as well. The staff discusses everything from nutrition to heart function and stress reduction. Very little of it is new to me, but every session I walk away with a nugget of information that has helped me change my perspective and improve my life.

For example, if you had asked me six months ago if I was stressed, I would have told you no. I mean we all have stressors, but I didn’t think it was affecting my life. Boy, was I wrong. As it turns out, low-level stress that never gets relieved like constantly worrying about money or stress at work is equally as problematic as larger stress event like a divorce, or a marriage or losing your job or buying a house.

On the nutrition side, I’m gaining a stronger understanding of how I should be eating and what bad choices do to my body. We all know we should eat better, but knowing that we should and knowing why we should are often two entirely different things.

How Your Waist Measurement Can Indicate Heart Disease Risk

I’ve always been skeptical about Body Mass Index. While it may work in very broad terms, people who carry a lot of extra muscle, for example, end up with really high BMIs, but they aren’t fat. I remember hearing one time that Arnold Schwarzenegger was obese, according to his BMI. The scale is an attempt quantify a person’s mass (weight) based on their weight. There are mathematical calculations for it, but there are also charts and online calculators that can give you your BMI. Commonly accepted BMI ranges are underweight: under 18.5, normal weight: 18.5 to 25, overweight: 25 to 30, obese: over 30.

Risk factors for heart disease include obesity and high cholesterol, as well as family history and smoking, but one nugget I picked up is that waist size can be an indicator of a person’s risk for heart disease. A simple measurement of your midsection can indicate whether or not you have an increased risk of heart disease. It doesn’t matter if you are short, tall, heavily muscled or rail-thin — it’s just about waist size.

I found several different references for this, but I liked this one from Canada’s Heart and Stroke Foundation best.

Are You At Risk?

| GENDER | INCREASED RISK | HIGH RISK |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 37 inches or more | 40 inches or more |

| Female | 31.5 inches or more | 35 inches or more |

Some ethnic-groups or people living with risk factors may have increased risk even at lower waist circumference measurements.

According to Heart and Stroke’s website: “Having a waistline that is below the cut-off does not mean you are completely free of risk. Your individual risk can be influenced by your health, medical history and family history, so the universal cut-points in the chart can be misleading. If you have other risk factors, like diabetes, high blood pressure, or high cholesterol, you might need to lower your waist circumference to minimize your risk. Reducing your waist circumference by 1.6 inches (4 cm) can have massive benefits to your risk profile and reduce your chances of developing diabetes, heart disease and stroke.”

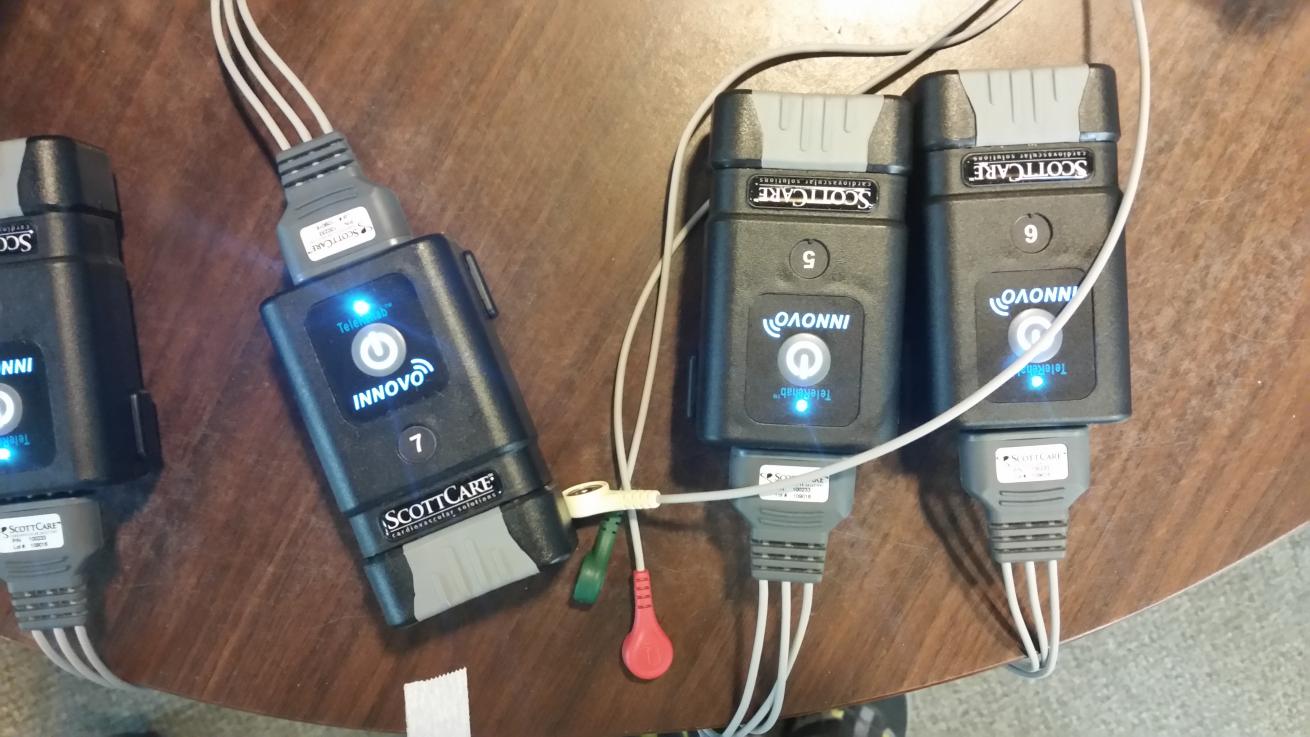

Courtesy Eric DouglasVarious monitors are used during cardiac rehab to monitor a patient's vitals.

Belly fat indicates high levels of fat around your internal organs and according to an article from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, “If most of your fat is around your waist rather than at your hips, you’re at a higher risk for heart disease and type 2 diabetes.”

And an article on WebMD quoting Nieca Goldberg, MD, medical director of the New York University Langone Joan H. Tisch Center for Women’s Health said “A thicker waistline increases heart attack risk. Stomach fat is linked to high blood sugar, increased blood pressure, and raised levels of triglycerides, a type of fat in your blood. All of these are major risk factors for heart disease.”

HOW TO MEASURE

You can’t judge your waist size based on your pant size, because odds are good that your true waist will be larger. The following is how to measure your waist.

1. Find the top of your hip bone and the bottom of your ribs.

2. Breathe out normally.

3. Place the tape measure midway between these points and wrap it around your waist.

4. Check your measurement.

If you aren’t sure if you are at risk or not, get out a flexible tape measure and measure your waist. If you are above a 40 (or 35 for women) I highly recommend that you call your doctor and get checked out, even if you are symptom free. While you are waiting for that appointment with your doctor, start working on the risk factors, like smoking, diet and exercise.

I have no family history and none of the other risk factors, but my waist was above 40. And I ended up with a quintuple bypass.

Read the Full Series Here

Author’s Note:

Since 2009, I’ve written the Lessons for Life column for Scuba Diving magazine providing analysis of scuba diving accidents so others can learn from them — and hopefully avoid being in the same situation.

In the ultimate Lessons for Life, I invite you to follow along as I write about my personal experience with coronary artery disease, open heart surgery and the recovery process over the next few months.

Eric Douglas co-authored the book Scuba Diving Safety and has written a series of adventure novels, children’s books and short stories — all with an ocean and scuba diving theme. Follow him on Facebook or check out his website at booksbyeric.com