Don't Push Freediving Limits | Lessons for Life

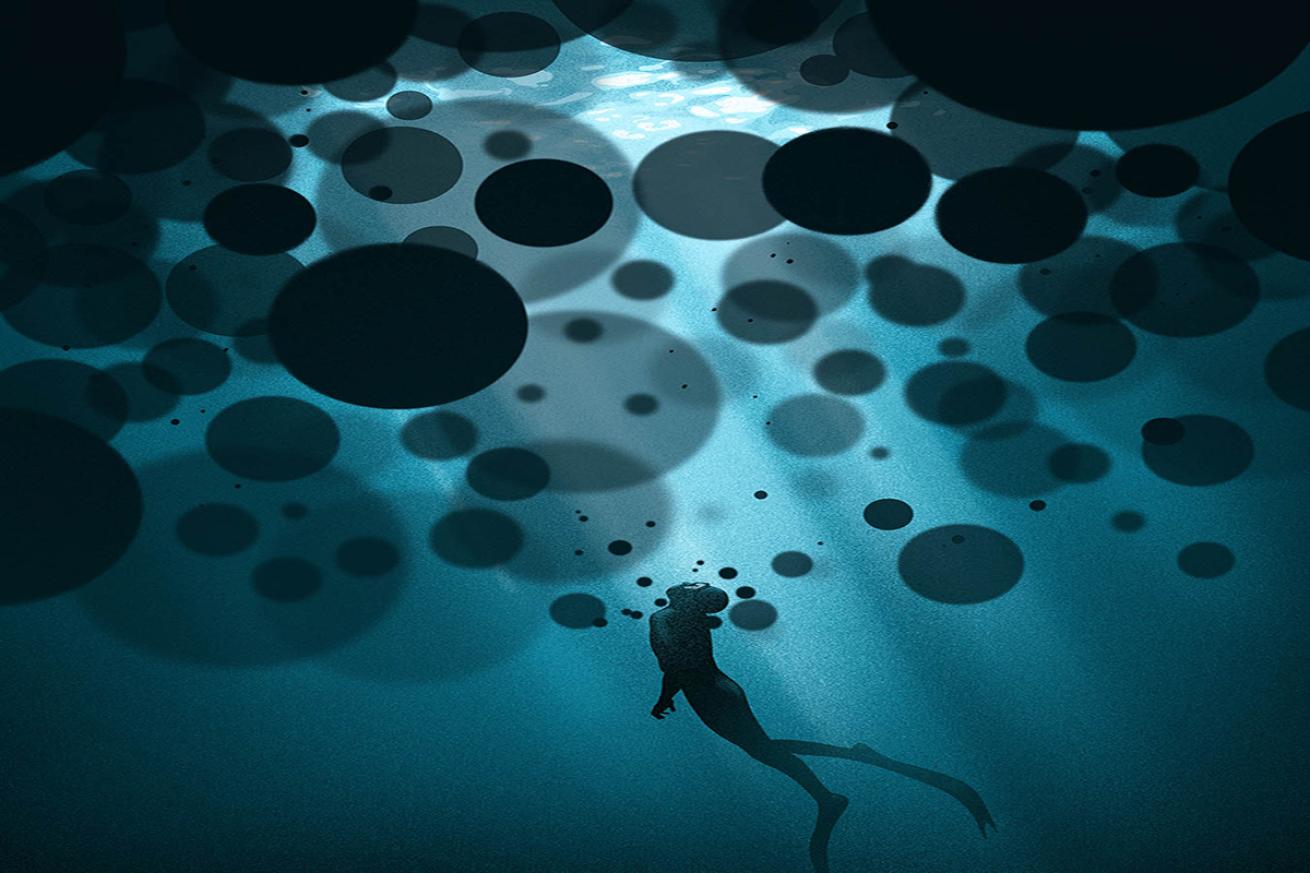

Carlo Giambarresi"Around 30 feet from the surface, Stephan’s ascent slowed and then stopped."

Stephan was excited to be freediving with Mark, who was four years old- er and a lot more experienced. Stephan wanted to learn to dive as deep and stay down as long as Mark could.

They prepared themselves on the surface, and Stephan followed Mark underwater. Stephan watched Mark swim along the reef and did his best to keep up, but his movements weren’t as relaxed. He could feel the urge to breathe getting stronger, but he hated to surface ahead of Mark. He didn’t want the other diver to think less of him. Finally, Stephan couldn’t wait any longer and began swimming upward. Just before he reached the surface, his vision grew cloudy and dark.

THE DIVERS

Mark was a 20-year-old freediver. He was in good health with no known medical conditions and maintained a high level of fitness. He had been freediving for five years. He wasn’t competitive but was comfortable diving to 100 feet of sea- water or more. He enjoyed the freedom it gave him, exploring local reefs without tanks and dive gear, although he was also a certified diver.

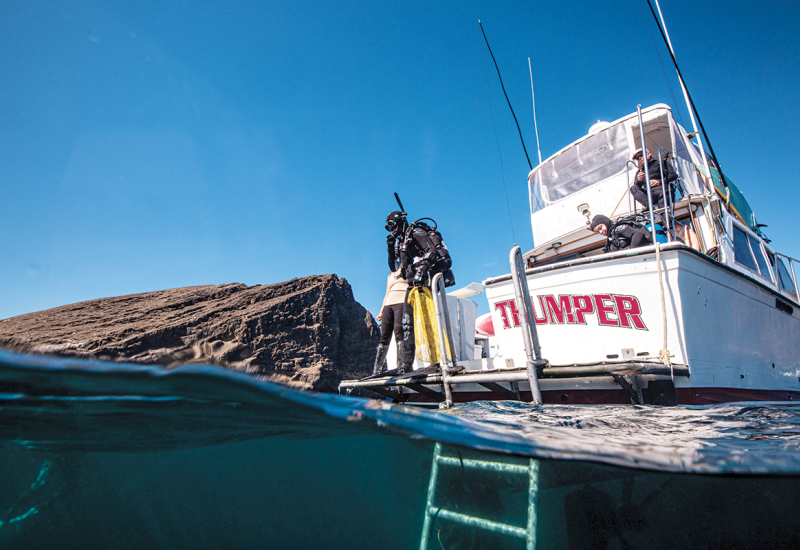

Stephan was a 16-year-old in good health. He was new to both scuba diving and freediving. He had met Mark at the local dive shop; Stephan had asked Mark to go diving with him several times be- fore Mark finally agreed. They planned a trip on a local charter boat that was used to working with freedivers.

THE DIVE

Conditions were perfect. Water and air temperatures were warm, and the ocean was flat and calm. There was minimal current on the reef below them.

On the boat, Mark showed Stephan how to weight himself to make it easy to get to depth, but also easy to return to the surface. In the water, they did a buoyancy check to make sure they were positively buoyant with empty lungs at 30 feet of seawater.

After Mark was satisfied with Stephan’s weighting, they did a few shallow warm-up dives so Mark could make sure the younger diver knew what he was doing. After that, they went to the reef.

The bottom was about 90 feet down. Mark was used to dives at that depth, but it was at the edge of Stephan’s abilities. The divers signaled each other they were ready, and both young men began their descent.

THE ACCIDENT

Mark led the dive but regularly looked behind him to check on Stephan. After a minute at depth, Mark noticed Stephan begin his ascent. He decided to follow to make sure Stephan was all right.

Around 30 feet from the surface, Stephan’s ascent slowed and then stopped. Mark could tell Stephan had lost consciousness. He immediately moved in and began towing Stephan upward.

Just before they both reached the surface, Mark lost consciousness, blacking out just a few feet from safety.

The crew on the dive boat was scanning the water and saw two bodies float to the surface; neither diver appeared to be moving. They quickly jumped in and swam to the stricken divers. They turned them face up and towed both young men to the boat. On board, the crew began CPR, and both divers began breathing on their own. They were taken to the hospital, and both men made a full recovery.

ANALYSIS

Freediving is a calm, relaxing, beautiful way to experience the underwater world. But it comes with a unique set of risks.

Shallow-water blackout, known as hypoxia of ascent, occurs when divers deplete the oxygen in their blood and body tissues at depth. Ambient pressure from the water raises the partial pressure of oxygen in the body, making the declining oxygen reserves able to sustain life while he diver remains at depth. Ascending to the surface causes the oxygen partial pressure to drop quickly, which can cause a diver to lose consciousness in the final few feet before breaking the surface.

Mark’s attention to weighting likely saved both young men from drowning. They were weighted defensively, ensuring that they were positively buoyant as they neared the surface, when they were most likely to need it. The momentum Mark provided Stephan once he began swimming both of them to the surface likely helped as well.

Being positively buoyant made it easier for the crew to see them and realize they were in distress. If they hadn’t been buoy- ant, they might have stopped a few feet below the surface and drifted away, un- seen by those on the boat.

On the other side of the coin, the additional work and physical stress of saving Stephan likely caused Mark to black out as well. If he had been surfacing alone at his normal pace, he would likely have made it to the surface without a problem.

A common safety protocol for freedivers is the “one up, one down” technique. With two divers in the water, one diver swims down while the other stays on the surface and watches, escorting them through the final part of the ascent and responding if there is a problem. This also provides a break for the diver on the surface to relax and prepare for the next dive.

In years past, freedivers learned to hyperventilate prior to making a dive, but that is no longer recommended. Hyperventilation postpones the urge to breathe by purging the body of carbon dioxide. CO2—not oxygen levels—triggers the body’s breathing response.

If a diver hyperventilates and stays at depth too long, it increases the chance of blacking out. Freedivers today are trained to relax and dive without hyper- ventilation. The best way for divers to increase their bottom time is through small, incremental increases in depth and time, be- coming accustomed to how long they can delay surfacing and improving their diving abilities.

As with any water sport, freediving requires training and practice. Divers should also maintain a high level of fit- ness, so their bodies function at peak performance. One or two quick trips underwater as a snorkeler is usually not a problem. It’s when freedivers begin to push their limits, go deeper and stay at depth longer that they need to take additional safety precautions.

Modern freediving courses often use techniques like meditation and yoga to help divers fully relax prior to a dive. Minimizing jerky movements and swimming slowly prolongs the dive.

LESSONS FOR LIFE

- Seek training. If you want to move from being an occasional snorkeler to a freediver, take a class and learn the proper techniques to do it safely.

- Follow safe freediving techniques. Don’t dive alone. Have a buddy on the surface, and weight yourself properly.

- Don’t push your limits. Make gradual ex- tensions to the depth and time of your dives so you can return to the surface safely.