Underwater Photographer Thomas Peschak Joins Scuba Diving’s Sea Heroes

Our Sea Hero program celebrates divers working to save our seas through action-oriented education, conservation, exploration or innovation. Nominate a Sea Hero

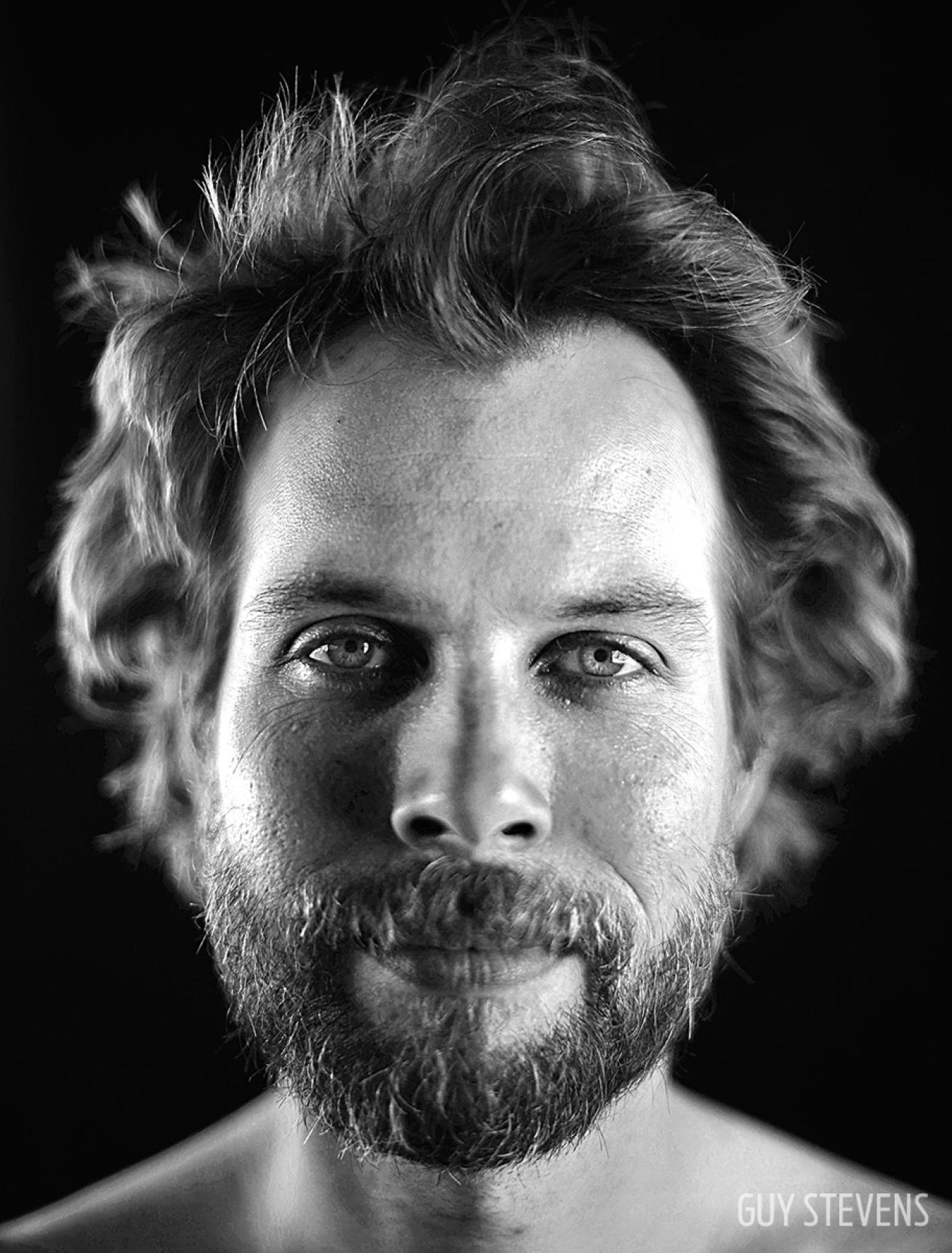

Courtesy Guy StevensThomas Peschak is a conservation photographer who has been diving since 1990.

Thomas Peschak is a globally recognized photographer for National Geographic magazine who inspires millions with his images. But it’s his marriage of marine science — as director of conservation for the Save Our Seas Foundation and associate director of the Manta Trust — and a passion for making critical conservation questions important to everyday people that makes him our September/October issue Sea Hero.

Q: You describe your mission as merging photojournalism and cutting-edge science — why is that important to you?

Photography has been a passion for as long as I can remember, but I actually studied marine biology, intent on contributing to ocean conservation through scientific research. From the coral reefs of northern Mozambique to the seagrass beds of Central America, I was fortunate to lead an adventurous life as a field biologist. Yet after a decade I discovered that even the most overwhelming scientific evidence doesn’t necessarily lead to acts of conservation. For instance, as a graduate student I researched the impacts of South African abalone poaching, fueled by the demand from international crime syndicates. I discovered that the scientific data showing decimated abalone populations were not being considered in protection measures. On the other hand, the response to the photographs I took during the course of my research, which showed poaching and seascapes devoid of life, was much more visceral and immediate. I quickly realized that I could help further conservation efforts more through my photographs than through statistics. So I left behind a marine biology research career for the nomadic life of a photojournalist. Science however remains integral to my life as a photographer. The most exciting natural history stories, new wildlife behaviors and most critical conservation issues are found in the scientific literature, often hidden by jargon and technical complexities. My role is that of a translator, who transforms complex science and conservation topics into iconic photographs. I try to create images that change my audience’s relationship with the ocean for the better.

“It has become my life’s work to create images that inspire people to act.”

Q: You've said that your shots walk a fine line between "disturbance and inspiration" — how do you find and hold that line? Why does that matter?

I spend up to 300 days a year away on photographic assignments and for about half of that time I visit beautiful places and take images that celebrate the ocean and hopefully inspire people. On the other 150 days I document the darker side of our relationship with the sea. For me, conservation photography is all about the carrot and stick approach. One way to make people feel something for an animal or an ecosystem is to inspire them, show them something that makes them go “Wow! I didn’t know anything like that could exist.” You can say, ‘this is what is at stake and what we still have to protect.’ It’s about nurturing a connection between the audience and the natural world. The risk with this approach is that you can create the impression that a sustainable future for biodiversity has already been secured. This can make some people complacent. The truth is that the wonderful Edens of biodiversity that appear in wildlife documentaries or magazine articles are only a tiny fraction of our planet. The reality is that our exploitation of the natural world is having an incredibly detrimental and destructive impact. We’re at a point where our actions have shaped the planet as much as geological processes. As a photojournalist, it is my job to accurately reflect this reality. So, the other half of my year I spend my time photographing the realities of rampant overfishing, marine pollution and the impacts of climate change on our oceans. This is not something people want to face and they try to avoid images that portray this reality. It’s a challenge, but just because they’re hard-edged and hard to look at does not mean these photographs cannot be beautiful. As a conservation photographer, I had to learn to create engaging imagery of the darker side of things. The challenge lies in how to create beautiful imagery from a haunting reality. I always walk a fine line between trying to inspire and disturb! Too much inspiration and people can get complacent, too much doom and gloom they become overwhelmed with hopelessness. My aim therefore is to tell balanced and honest photo stories that get people to think, act and ultimately make a difference for example by changing the fish they eat or what they throw away.

Thomas PeschakSilky shark carcasses await auction at a port along the Arabian Sea.

Q: You have a wonderful quote on your web site about photographers teaming up with NGOs and scientists: "A lone wolf at best can tackle rabbits or small deer, but a wolf pack can take down a 1300-pound moose." How do you make that kind of collaboration happen?

I have always been a very driven person, and for the longest time I was a complete control freak. I always wanted to lead the charge on every facet of every project. However with age (I turned 40 last year) and experience comes a certain degree of maturity and the healthy realization that I cannot do it all. I have strengths as well as weaknesses and these days I try to play to my strengths and collaborate with talented people who are amazing at the things that I suck at. There is an old African proverb that says: If you want to go fast, go alone, if you want to go far, go together. Nowhere is this truer than in conservation photography. The greatest conservation victories can only occur when photographers team up not only with scientists and NGOs, but also with videographers and other artists. Most of my collaborative projects are channeled through two organizations the Save our Seas Foundation (of which I am the Director of Conservation) and the International League of Conservation Photographers, of which I am a Senior Fellow. My collaborations usually center on long-term projects that are simply too complex for a single photographer to successfully pull off on his or her own.

Q: You were a marine biologist before you became known as an award-winning photographer; does that science background change the way you approach your art?

Once a marine biologist, always a marine biologist. While I have hung up my active research and scientific publishing boots (fins), marine biology still underpins almost everything that I do (See answer to question 1). I also still spend about 25% of my time in the capacity of a conservation scientist. For the Save our Seas Foundation as Director of Conservation and as Founding/Associate Director of the Manta Trust.

Thomas PeschakBlacktip reef sharks wait for the tide to refill the lagoon at remote Aldabra Atoll in the Seychelles.

Q: What is the biggest challenge you have faced in your work in marine conservation? What do you view as the most critical issues in marine conservation today?

When I began working as conservation photographer 15 years ago, dramatically declining shark populations and in particular shark finning were one of the most critical marine conservation issue. By focusing on iconic sharks (great white, tiger, bull, whale, etc.) I hoped that conservation benefits would also cascade down the food web and ultimate ensure that entire marine ecosystem would be protected and remain healthy. While sharks still face huge challenges, many important shark conservation milestones, both popular and scientific have been successfully reached. After the 2014 publication of my book Sharks and People (my 10 year retrospective of shark photography and conservation) I have somewhat backed off from continuing to tell the stories of the well-known shark species and began focusing on a completely different group of sharks. Sawfish, angel sharks and guitarfish, the “Lost Sharks” are the most threatened elasmobranchs on the planet, yet few people have heard of them. For example few people realize that all five species of sawfish are currently listed as endangered or critically endangered. Today it is these more obscure species that require the greatest public support for protection. However, with only a handful of good images of sawfish in the wild, how can we expect to inspire the urgency to conserve them? It is this conservation photography “black hole” that I am currently trying to fill. This ambitious 3-year project has many scientific, conservation NGO and media partners. I am not only documenting the behavior and ecology of the Lost Sharks, but I also focus on the complicated relationship they have with people, from commercial fishermen that exploit them to indigenous communities that revere them. My aim is to create a compelling visual narrative that will introduce these sharks to the world and establish them as critical components of the marine realm. I want them to take their rightful place alongside the better-known shark icons. The Lost Sharks are incredibly difficult to find and photograph and this might be the single hardest project I have ever undertaken, but it also is one of the most critical and urgent challenges in shark conservation today.

Q: What's been your most satisfying moment?

While I am very proud of my eight feature stories that I have shot for *National Geographic Magazine *and the downstream conservation benefits they have elicited, my proudest achievement is creating the Emerging Marine Conservation Photography Grant for the Save Our Seas Foundation. To ensure that photography continues to raise awareness of critical marine conservation issues we have to urgently invest in the marine conservation photographers of the future. Media budgets are continually shrinking and it’s becoming economically more difficult, especially for less established photographers, to tell stories with real conservation value. I think we’re losing a lot of great young photographers to other, perhaps more financially reliable careers.

My aim with this grant is make a small contribution towards changing this. Not only do I want to mentor, uplift and drive the next generation of conservation photographers, I also want to give them a chance to tell honest, balanced and engaging stories that make a difference. So please check out: www.saveourseas.com/photogrant

Q: Tell us a little bit about what you are working on now? What's next for you?

Late in 2016 I am scheduled to begin work on my 10th story for National Geographic Magazine. I can’t really say too much about it, except that it tackles critical global marine conservation issues from a totally different and fresh perspective. With this story we are reaching out to a completely new demographic and it is my hope that we will engage at least 60 million new advocates for ocean conservation. The end of 2016 will also see the publication on the world’s first book on manta rays, a project that combines incredibly insightful text from Manta Trust director Guy Stevens with my manta photographs shot during many expeditions over last 8 years. Of course there is also the “Lost Shark” Project, about which I reveal more in my answers to question 5.

Guy StevensPeschak freedives with a feeding chain of reef mantas in the Hanifaru marine reserve, Maldives.

Q: How can Scuba Diving's readers help further your work?

I truly believe that scuba divers and snorkelers are the frontline of marine conservation. I realize that many people feel that they don’t have the power and necessarily influence to make a difference in shark or marine conservation. Nothing could be further from the truth. Obviously if you regularly consume shark fin soup or blue fin tuna, then curtailing that behavior would be a critical step, but even those who don’t eat the above can have detrimental impacts. Many of the marine species we regularly eat, like shrimp/prawns for example comes from fisheries that not only have a large bycatch component but also use gear that directly damages the seabed. You can educate yourself and become more intentional about the kind of fish you order at a restaurant or put on your dinner table. Ask questions, think, and be selective. It’s difficult to turn down certain seafood dishes, especially if it is a habit. But as a consumer you have massive power to change the way markets and restaurants do business and make it ripple all the way up the supply chain and straight back to the fishermen. Most critical however I feel is to try and gain a truthful and balanced insight into our oceans, the animals that inhabit them and the conservation issues they face. That way you can pass on this knowledge to your friends and family.

Q: What would you do with the $5,000 cash award if selected for Sea Hero of the Year?

I would divide the cash award into mini-grants of US $1000 each and give them to five young emerging conservation photographers from the developing world. Life can be difficult enough for an emerging photographer in North America or Europe, but downright impossible for young photographers based in Africa, Asia or Latin America. These mini grants would allow them to continue photographing a important local conservation story and allow them to further develop their craft.

Q: Is there anything we did not ask that you would like readers to know about? Tell us what's important to you!

The legendary conservationist George Schaller wrote, “Pen and camera are weapons against oblivion, they can create awareness for that which may soon be lost forever.” Schaller’s words are my mantra and inspire me to keep working for change. Photographs, I believe, are one of the most powerful weapons in the marine conservation arsenal, and it has become my life’s work to create images that inspire people to act. To be successful as a conservation photographer, you have to be obsessed with creating images and telling stories that matter. It’s also essential to try to make original and memorable photographs. My editor at National Geographic Magazine, Kathy Moran, regularly encourages me with the following words, “Show me something that the world has never seen before or something that everybody is familiar with but in a way so different that people will be convinced they’ve never seen it before.” Conservation photography can be an emotional roller coaster. It can be socially isolating, logistically exhausting, and physically demanding, yet it is also the most emotionally and professionally rewarding pursuit that I can imagine. To survive and thrive in this profession you have to be a hopeless optimist, believing that the next great picture is just around the corner, behind the next coral head, or mangrove root or…. just behind the one after that. It’s not just the photography. It’s the drive. It’s the commitment. It’s the obsession with the subject. You have to be certifiably insane to make it in this game. That’s the reality. You have to want it so badly and you have to be in love with the process, with the research and with the science. You have to be hungry. Really REALLY hungry to make difference.

Each Sea Hero featured in Scuba Diving magazine will receive an Oris Aquis Date watch worth $1,650. In March 2017, a panel of judges will select the 2016-2017 Sea Hero of the Year, who will receive a $5,000 cash award to further his or her work.

.png?itok=wW_XQefZ)