Adventuring Through Oz

Once upon a time, questing for dragons was standard hero fare, a path trod by Perseus and St. George and their ilk. Following in their footsteps, how can we not take heart as we prepare to write our own undying saga of diving headlong into an invasion of giant spider crabs? Yet this bold endeavor is but a million-legged, courage-proving prelude.

But we forget ourselves. In true bardic tradition, let us relate the story that gave birth to our undertaking at the bottom of the world in southern Australia, in the teeth of winter.

“Our anniversary is coming up,” said she. “Exactly,” said he. “Girls want to see blue devils and deadly krakens. Girls want to fly with dragons.”

He answered: “There is but one place where such fantasies become real: the Land of Oz. Expect great hardship, drysuits, shore entries and endless driving. Envision the mother of all road trips, with sensational diving, unimaginable marine life and fickle weather, with toil and trouble lurking around each corner. Like our college days, but in middle age.” “Bring it on,” said she.

Brandon and Melissa ColePlenty of ground was covered during the 26-day journey.

DAY 1: June 6

We’re the proud new owners of a deluxe garden cart, purchased from a big-box hardware store only a few klicks—kilometers, for the metrically challenged— from the Melbourne airport. Henceforth, this essential piece of kit shall be known as our battle wagon, and I relish the thought of repeatedly overburdening it with mountains of spine-deforming equipment.

Google helps us navigate the rental van—never again will it be this clean—southward for 90 minutes to the Mornington Peninsula and the town of Rye. The Scuba Doctor dive shop has just what the doctor ordered: six steel tanks and 80 pounds of lead. The damage for our four-week rental is a cool 1,000 bucks. Ouch. The beasties better be worth it.

Brandon ColeHundreds of giant spider crabs amass at Blairgowrie Pier.

And oh. My. God. Words cannot capture the majesty of the giant spider crab army entrenched under Blairgowrie Pier. On our very first dive, my anniversary present is delivered in spectacular—some might say creepy—fashion. A seething, chittering mass of thousands upon thousands of crabs is stacked 10 to 15 bodies high on the sand, clambering over one another and oblivious to our presence.

Each winter, unfathomable numbers of these basketball-size crustaceans march up from the deep to congregate in the shallows of Port Phillip Bay to upgrade their armor, molting en masse. Blairgowrie and nearby Rye Jetty are two easy, shallow shore entries where the spectacle often unfolds around the full moons in May and June. We don’t see molting on Day 1, but with a bit of lunar luck we’ll witness the main event in the weeks ahead. For now, we have more than enough to enchant us during multiple two-hour dives to 16 feet in 54-degree water. In addition to the spideys, the pier structure shelters abundant fascinating fish and invertebrates, many of which we’ve never seen before: big belly seahorses, short-tailed nudibranchs, cowfish, globefish and banjo rays.

High point: Crabageddon! Low point: Melissa’s drysuit is leaking.

Brandon ColeMelissa Cole packs into the van with loads of dive gear.

DAY 3: June 8 (world Oceans Day)

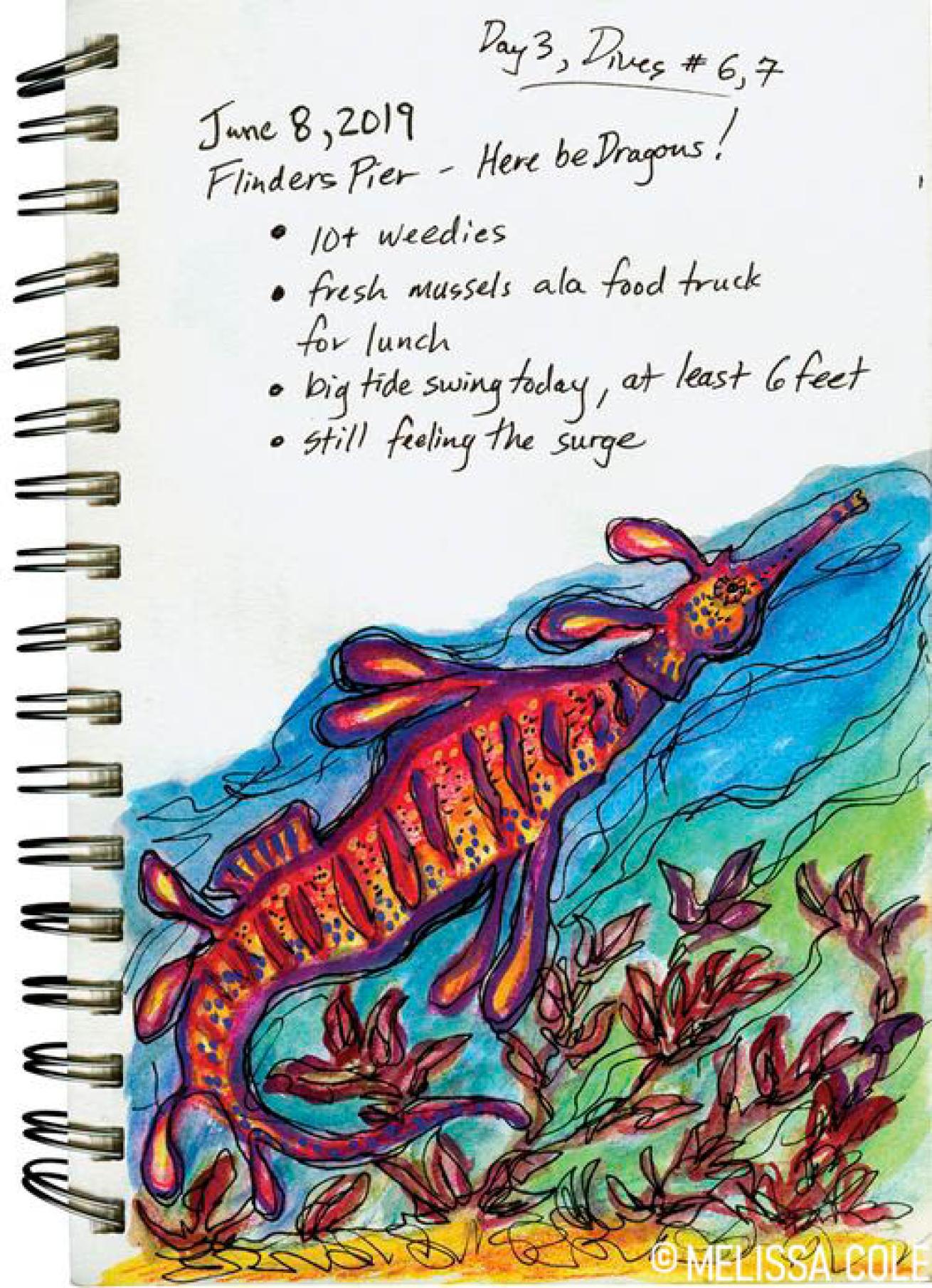

With strong northerly winds mucking it up at Blair, we decide to hit the road. I’ll miss the crabs, but not our more-than-a-bit-odd Airbnb host—not Jack Nicholson-in-The Shining odd, but definitely a strange kettle of fish. We pile everything into the van and drive 45 minutes to the southern side of the peninsula to find flat seas at Flinders Pier, haunt of the common (aka weedy) seadragon.

Phyllopteryx taeniolatus is anything but commonplace. The official marine emblem of the state of Victoria is an unbelievable creature worth traveling from the other side of the planet to see. Start with a seahorse; stretch it out to 15 inches long, then paint with sienna and canary yellow, accenting with rakish purple bands and a constellation of white-and-yellow polka dots. Finish by attaching teardrop-shaped fin fronds to its head and body, sprouting at jaunty angles to give this fish an air of elegant weirdness. Utterly spellbound, we fly alongside a handful of dragons as they glide over the seaweed, pausing every so often to slurp up tiny mysid shrimps with their trumpetlike snouts. Ferocious to its prey, certainly, but to us a magnificent monster we’ll always hold close.

Melissa ColeWeedy seadragon

Instead of mysids, we dine on fresh, locally harvested mussels with spicy-sweet laksa sauce served piping hot from a food truck in a parking lot. Scrumptious. Warm again, my wife, Melissa, and I swap tanks, waddle back down the hill, out onto the jetty, down the steps, and hop back into the drink, where we observe more dragons bounding over the seascape like aquatic dreamtime kangaroos come to life.

Brandon ColeA weedy seadragon swims over sea grass. This relative of the seahorse can grow up to 18 inches in length and is found only in Australia.

Poring over photos in a new and improved Airbnb, we realize we encountered somewhere between eight and 12 different seadragons today. We email images to Kade Mills, a marine biologist with the Victorian National Parks Association. He runs the Dragon Quest program, which utilizes the same app used to ID whale sharks to map the spots on a seadragon’s flanks, then compares the unique fingerprint-like pattern to images in a database. Thanks to citizen science, Mills has identified more than 150 individual dragons at Flinders so far. A better understanding of local seadragon populations is vital to implementing appropriate, effective conservation measures to ensure the survival of this marine icon, an endemic species living only in southern Australian waters. Divers are handsomely incentivized to contribute to Dragon Quest: New weedy seadragons are named after whoever discovers them. How cool is that? I fall asleep dreaming of my future fame.

Day 4: June 9

The day dawns with heavy, steel-gray skies and fresh winds lashing the Mornington Peninsula. Melissa is less than enthused about our scheduled offshore outing with RedBoats.

Brandon ColeThe stern of the HMAS Coogee.

With groaning battle wagon in tow, we lean into the blow, squint against sheeting rain, and trundle our way a few hundred yards to meet a cadre of ocal tec divers at Portsea Pier. We’re the only ones not sporting rebreathers or sidemount rigs. No matter. Warm Aussie smiles shine through the gloom, and they heartily reassure us this little squall is nothing: “Not at all uncommon during winter. The dive will be brilliant.”

Indeed it is. Though seas are snotty and the current spirited, the wreck of the Coogee is lovely. This 225-foot-long steamship was built in 1887 and given back to the sea in 1928, scuttled outside Port Phillip Bay in 115 feet of water, in an area crowded with dozens of shipwrecks known as Victoria’s Ships’ Graveyard. Nitrox 34 allows us to thoroughly explore the broken and battered vessel’s stern section, where Coogee’s imposing steering quadrant towers above ribbing and rudder, completely overgrown with golden zoanthids. Visibility is 30 feet, our max depth is 106 feet, and our bottom time is 35 minutes.

Brandon ColeA koala bear at Healesville Sanctuary near Melbourne.

High point: Not hurling on the boat, and not missing the down line to the wreck. Low point: Now both drysuits are leaking. We don Depend absorbent pads inside our suits.

Day 5: June 10

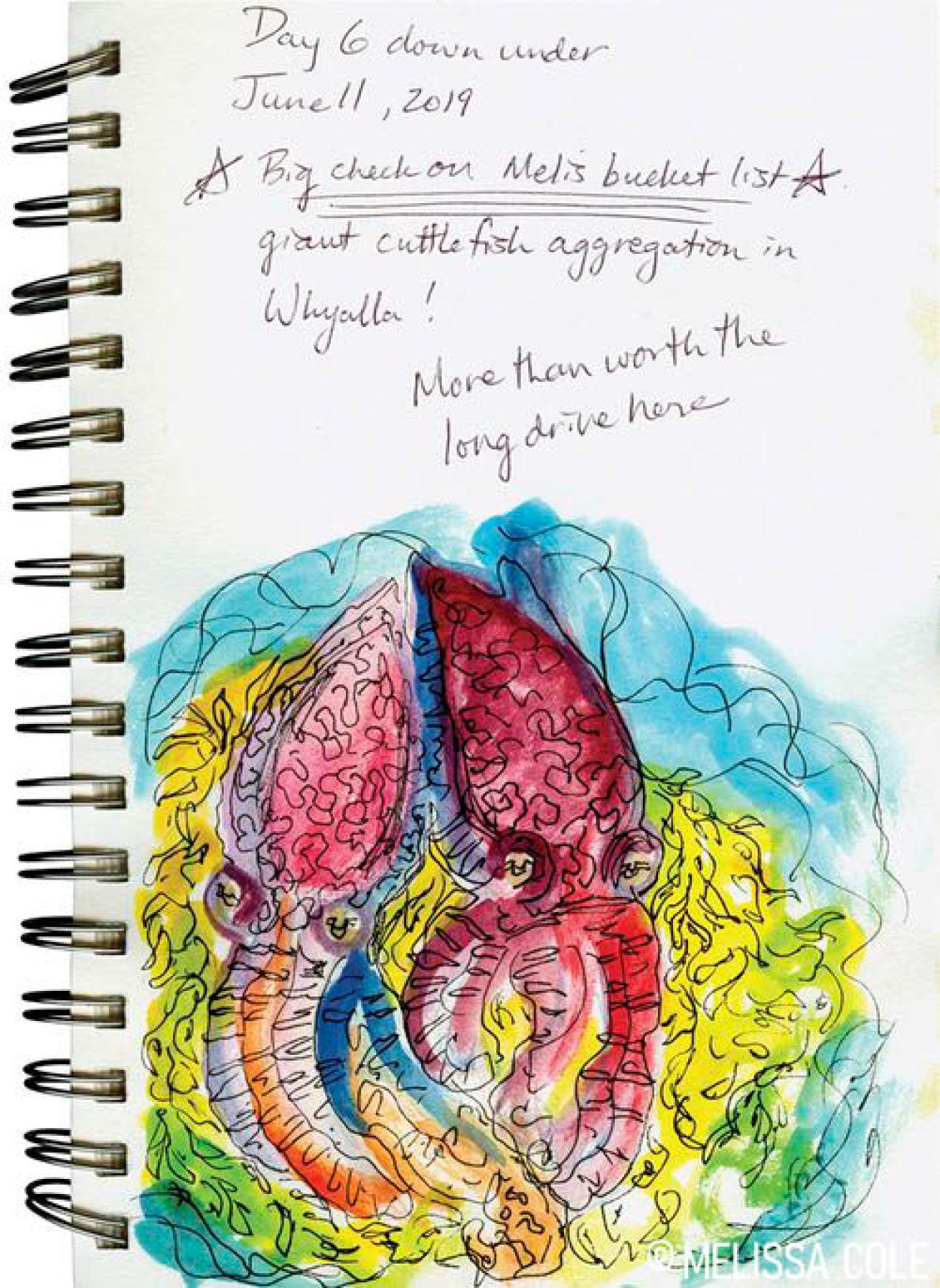

Melissa penning this one: Finally made it to Whyalla. Stony Point, actually, about 20 minutes out of town. We’re right at water’s edge. Completely exhausted, especially Brandon. Sixteen hours behind the wheel, and all on the wrong side of the road—except a few minutes now and then by mistake!—785 miles, including a few unintentional detours. And now we’re supposed to sleep in this van. I’m too old for this. (Almost.) Cuttlefish magic tomorrow, the most cuddly of my must-see monsters. I can’t sleep, so may as well write. If only this miserable seat reclined more, but we have too much junk in back. Are there scorpions in the outback?

Where to begin—the 50-foot-tall concrete roadside koala, or the yummy lamington sponge cake, a chocolate-and-coconut-covered confection from the gas station? Kangaroos and wallabies jumping across the road after dark? Or the expansive scenery, rolling green hills one hour and desert scrub the next? Working on seadragon sketches with my watercolor kit while Brandon waxed about what we’ll name our baby weedies? The most memorable thing today may actually be the hourlong chat on the side of the highway with a complete stranger. By the end of our rambling, our new friend Stefan was offering up his house in Adelaide if we needed a place to stay, or even just for a meal or shower. Tempting, that... We had stopped at a fruit quarantine bin at the border into South Australia to pig out on $20 of fruits and veggies we had just bought, rather than throw it all away or risk a ticket for smuggling foodstuffs. We talked with Stefan about white pointer sharks, the fact that his wife can trace her lineage back to Mehmed the Conqueror, sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and—here’s a handy outback tidbit—how to stay alive in freezing temperatures by putting steam-heated rocks in your clothes. Quite funny when he asked, “Why would you Yanks go to Whyalla?” His laughter boomed when we answered, “Calamari.”

Melissa ColeA sketch of cuttlefish.

Day 6-8: June 11-13

Whyalla is nirvana for underwater natural history photographers, sheer tentacled bliss for a cephalopod geek. The last three days at Stony Point have been even better than my visit 11 years ago—more animals, better conditions, and Melissa is with me to share in the cuttle magic. We’ve seen giant Australian cuttlefish courting, mating, inking, females depositing eggs, males fighting, and more. The electric light show of pulsating, rainbow colors when the big males—the largest are nearly 3 feet long—try to intimidate each other and impress the ladies is totally unreal, better than Hollywood CGI. So much behavior unfolding inches in front of us makes for unparalleled photo and video opportunities. Even the snorkelers floating above can see all the action, since everything is happening in only 3 to 12 feet. “I live for cuttlefish,” one local diver tells us. “When the season is over, I start counting the 45 weeks until they are back again.”

Brandon ColeGiant Australian cuttlefish, which can grow up to 3 feet in length, aggregate off South Australia to mate.

Only in wintertime, and only here. Scientists aren’t certain precisely where the tens of thousands of cuttlefish come from, or why they congregate only along this shallow, stony shoreline in the far northern reaches of Spencer Gulf. Breeding obviously has something to do with it. Stony Point and environs is critical spawning habitat, the only known cuttlefish mass aggregation site in the world. Its proximity to industry—there are oil and gas plants and mining operations in the gulf—makes it vulnerable to shipping traffic, potential toxic spills and other pollution, and then, of course, there is climate change and commercial fishing. It’s sobering to learn that just 20 years ago, overfishing decimated numbers from roughly 180,000 cuttlefish to only a few thousand.

Since then, a ban on harvesting has helped the population rebound. Scientists with the South Australian Research and Development Institute estimated 2018’s population at nearly 150,000. Tentacles crossed that these charismatic animals remain protected and allowed to procreate in peace.

Brandon ColeTent camping along the rocky shore near Whyalla for the cuttlefish aggregation.

I love camping out next to the water, waking up to apricot sunrises and flat seas—we’ve been first in and last out, 14-plus hours underwater in three days. So enrapt was I in capturing the life and times of Sepia apama I hardly noticed my leaky suit. Meli’s is worse. We need to buy more diapers when we go into town for air fills. The battlewagon continues to prove its mettle, a godsend in schlepping the gear up and down the ramp. I really want another day here, but the wind is forecast to clock around and blow southerly. Should be better over at Edithburgh.

Day 10: June 15

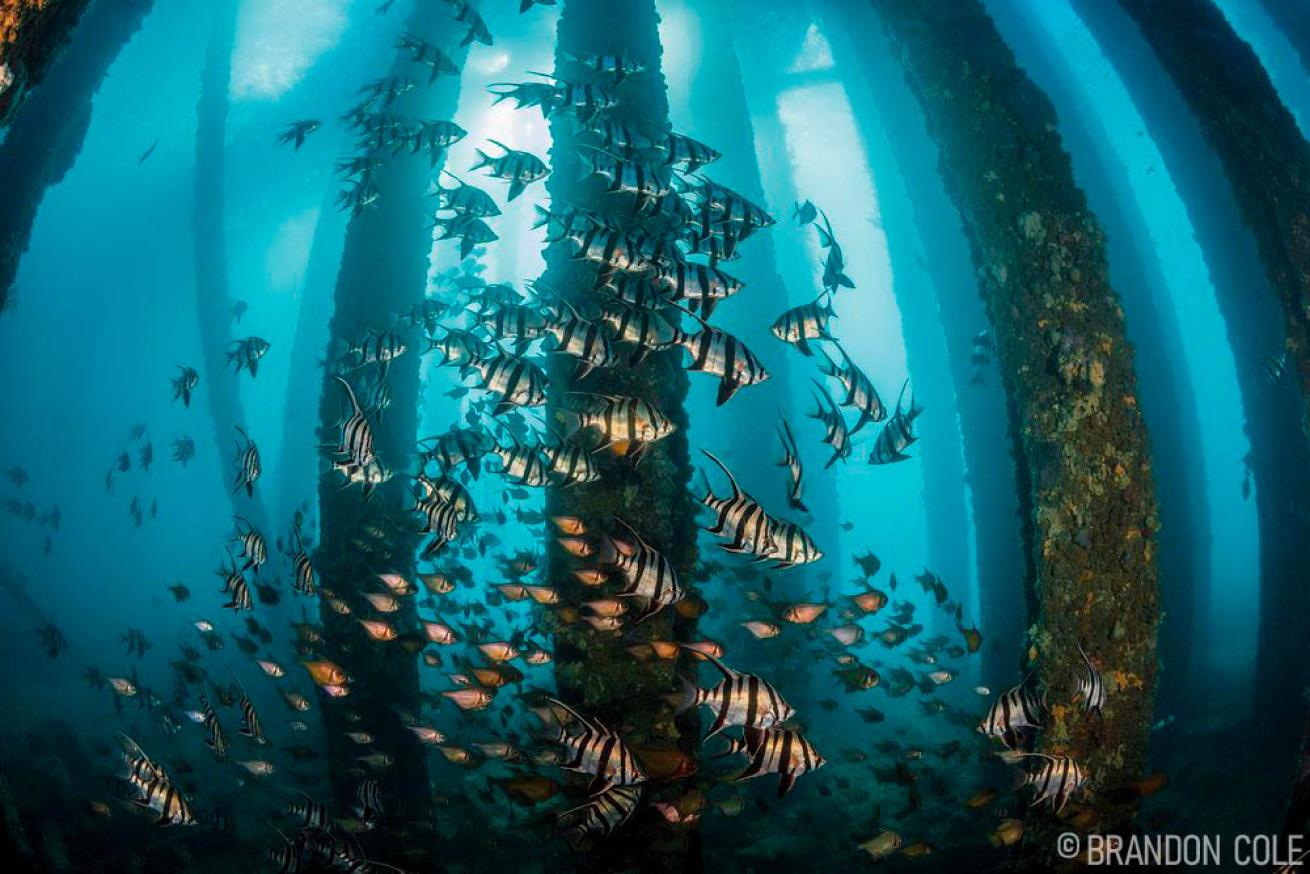

Brandon ColeOld wives and bullseye sweepers school among the pilings of Rapid Bay Jetty.

The jetties in southern Australia are extraordinary. Not only do they have stairs descending to the water, saving divers the hassle of slogging through surf, they are magnets for marine life. Edithburgh Jetty on the Yorke Peninsula is one of the marquee, must-dive jetty/pier sites. Our critter list positively overfloweth after just one dive in the jungle of pilings and crossbeams festooned with DayGlo sponges and tunicates. Superstars include an ugly-cute bearded yellow frogfish with a psycho stare, cute-cute clingfish peeking out of razor clam shells, and an intricately patterned leatherjacket hiding in plain sight against an invertebrate mosaic on a pylon. We also can’t forget the grumpy sponge crab rocking an orange beret and, to the eternal delight of my better half, not one but two blue-ringed octopuses (Hapalochlaena maculosa) cradling clutches of pearly eggs. Your deadly beauties, mon chéri. Happy anniversary!

We splurge with a powered campsite at the nearby Edithburgh Caravan Park and reminisce in the communal camp kitchen over a dinner of ramen and curry meat pies. It doesn’t get any better than this.

Brandon ColeTwo southern bobtail squid mate on the sandy bottom.

“Not true!” Melissa shouts later, taking the pen: “Brandon told me night dives here are remarkable, but wow! Finger-size shorthead seahorses on corkweed, their shiny tummies reflecting my light’s beam. Blue swimmer crabs brandishing wicked claws—a big, scary, mean-tempered one attacked Brandon’s camera! Sleeping baby filefish bumbling around. Six different species of squid and octos, including my first-ever striped pyjama dumpling squid, like a marshmallow in a prison suit! The corpulent little darling melted my heart.”

Day 11: June 16

Woke up to a rainstorm and leaking tent at 4 a.m. But even the deluge cannot dampen our spirits after last night’s amazing dives. Filled cylinders at Edithburgh Motors gas station—the only air fill station for 200 miles. Soggy today, then sun, then rain again. I charge cameras via the cigarette lighter. Lots of driving, about eight hours, back west again. We arrive at Port Lincoln at 8:30 p.m. and sleep in the van in the marina parking lot next to a port-a-potty.

High point: Thinking about those terrific night dives. Low point: Smelling the saltwater-soaked drysuit underwear warming up on the van’s dash.

Brandon ColeA view of Fleurieu Peninsula's rolling hills.

Day 12: June 17

Meli here. This chapter of MonsterQuest finds us in Port Lincoln, on the southern tip of the Eyre Peninsula, gateway to the Neptune Islands, domain of great whites. We join Adventure Bay Charters and depart before sunrise. Two and a half hours later, we slip into the cage, breathe from hookah regs and stare into blue-green space. Other passengers, still in their street clothes with beverages in hand, choose a view from the boat’s “surface submarine.” Even though Jaws is standoffish today—the few passes are at the edge of visibility—just being a same-ocean buddy with a white pointer is exhilarating. The weather forecast is sketchy for the next few days, so we cram ourselves back into the van and resume our nomadic dive life, letting the currents carry us where they will.

Day 14: June 19

Just as life on the road is beginning to wear, we receive a social media news flash that immediately re-energizes: Spider crabs are molting at Blair! (Yes, the spideys have their own Facebook page.)

No more whinging about driving hither and yon, trying to outsmart wind and weather, or sore eyes from long hours on kangaroo-avoidance duty, or flagging spirits due to never knowing when the next real bed and hot shower are to be had. Banished even is the odoriferous, unshakable specter of sodden drysuit underwear never far from our persons. Our resolve has been steeled. We have new purpose. We just have to backtrack 720 miles.

Day 15: June 20

Done. Ace underwater photographer and dive guide Sam Glenn-Smith meets us at Blairgowrie Pier. He reassures us, “You’re not too late. Heaps are gone, but it’s still going off. And Crystal is here!”

Brandon ColeGiant spider crabs cling to a pylon covered in sponges under Blairgowrie Pier.

It’s a war zone underwater. Molts are strewn everywhere, the discarded, empty husks of the crabs we met two weeks ago. Thankfully, there are still a few thousand live bodies as well, but the remaining Leptomithrax gaimardii are besieged on all fronts by huge, hungry stingrays. There must be 20. Some are easily 6 feet wide, gray-black with thick, rubbery wings, like giant, sinister portobello mushrooms delivering death from above. If they weren’t hellbent on devouring the newly molted crabs, temporarily vulnerable until their shells harden, I could almost root for the rays. I do cheer when Crystal swoops onto the scene—it’s not every day you see an albino stingray.

Clever crabs climb up pylons to hide under the jetty itself. Those out on open sand are likely doomed. But not this one! My eyes bulge when Sam directs us to the ultimate prize, a crab in the process of molting. The three of us form a protective cordon, vowing to fend off all predators. Stunned to be witness to this trial of life, we wait with bated breath for the next 20 minutes. Finally, freakishly, a new crab is born before us. Large and wobbly legged, it emerges backward from its old self. It’s truly an out-of-body experience, for both crustacean and the three privileged divers in attendance.

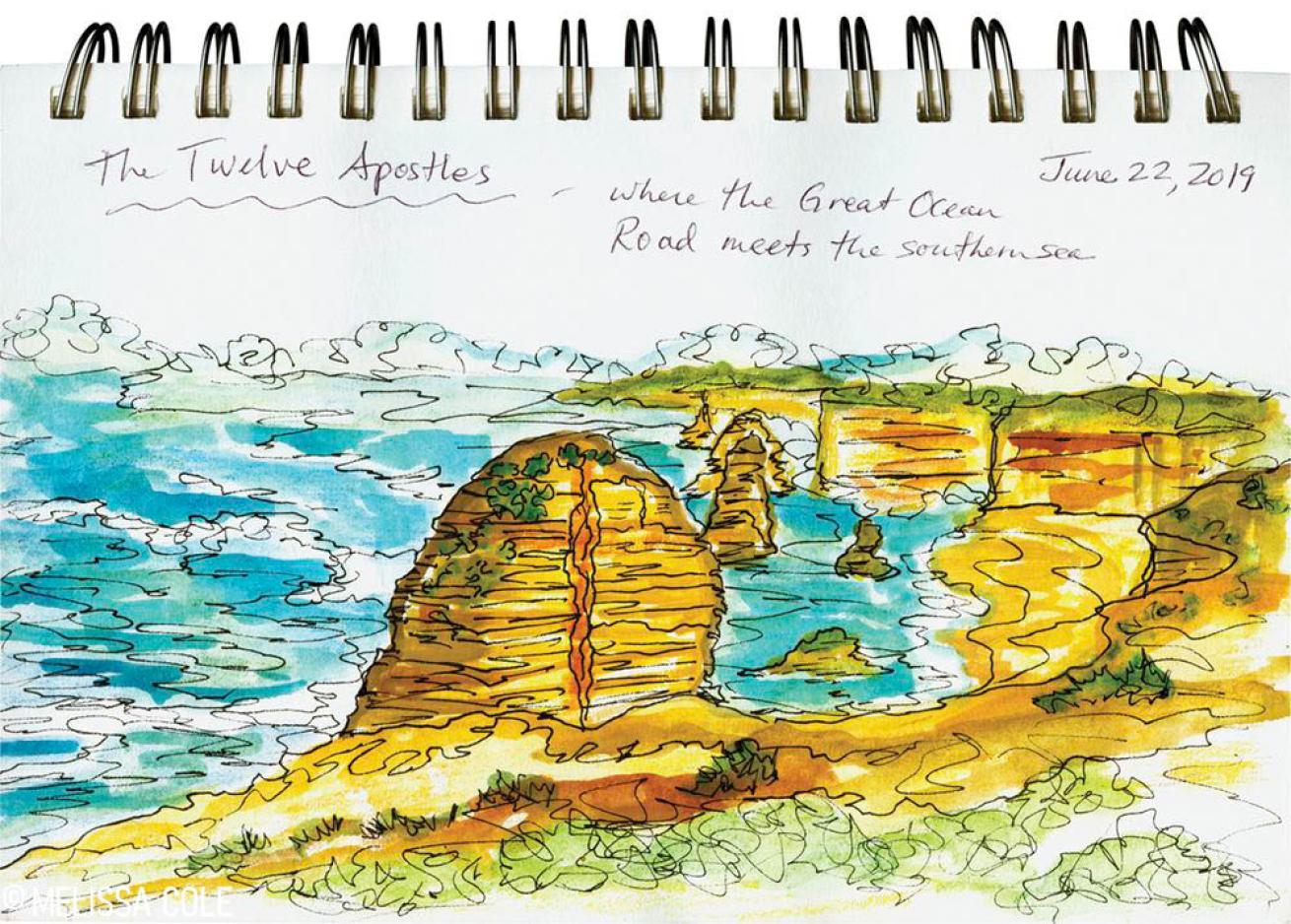

Day 17: June 22

Brandon ColeTwelve Apostles National Park

Heady with achievement, we’re on the move again, back to the west once more. In the spirit of adventure, we plot a longer, even more scenic route from Melbourne to Adelaide, eschewing the faster, straighter A8 interstate in favor of a spiderweb of twisting motorways, to immerse ourselves in Australia’s outback. The views along the Great Ocean Road are drop-dead gorgeous, especially in the Twelve Apostles Marine National Park, where sandstone sea stacks thrusting from the surf are the picturesque backdrop for many an Instagram selfie. We crisscross idyllic countryside where cows and sheep hold sway. Our GPS freaks out and sends us on a series of random reroutings—the area is a Bermuda Triangle for Google Maps. Frustrating, funny and fortuitous in the end, for on one of these byways we see a real live wild koala gamboling across the road.

Day 18: June 23

Meli here. Another day, another dive site—Second Valley, on the Fleurieu Peninsula—and a new and important mission. Late arrival last evening meant another sleepover in Chateau Minivan; I shivered for hours. It was zero degrees Celsius on the Down Under scale—that’s 32 degrees back home. A lovely, fiery sunrise, but still freezing.

While we’re gearing up, an Aussie bloke casually strolls into the parking lot and down to the water. He’s wearing a cowboy hat, shorts and gumboots. He shucks it all off and jumps into the ocean. At 7:30 a.m. With no thermal protection. I stare in amazement. After he emerges, I commend him on his fortitude. He downplays, answering, “I surf around here so I’m used to the cold water. It gets the day started right.” And here I am, all rigged up in drysuit and fancy Thinsulate 400-gram woolly bears (almost dry), whinging about the freshness of the morning.

Melissa ColeA sketch of Twelve Apostles National Park from a topside view.

Chelsea Haebich knows the state of South Australia beneath the waterline like few others. Professional guide, instructor and photographer, she has come down from Adelaide for the day to help us hunt dragons. She knows where they live, how to spot them and how best to interact with them.

I’m feeling woozy, staring at kelp swaying back and forth, when Chelsea coolly points to one of the tangles. What? Where? And then, voilà! Although I’ve been anticipating this watershed moment for 20-plus years, it still hits me like a ton of bricks when I realize there are googly eyes attached to that piece of algae. My holy grail—a leafy seadragon!—is levitating before me. So cunning is its camouflage, so impossible its design, man must submerge in the magical Oz to fully appreciate the magnificence of this fantastical fish. I can now die happy.

Brandon ColeLeafy seadragons blend in amongst Australia's aquatic plant life with frilled appendages.

Eagle-eyed Chelsea conjures three more Phycodurus eques out near the point, and a tasseled anglerfish to boot. Like the dragons of my dreams, this cryptic critter—a dourfaced, fist-size frogfish that causes B.’s heart to flutter—is endemic to Australia, living nowhere else on Planet Ocean. Only in Oz.

Hours later, after cleaning up to temporarily join the human race at Forktree Brewing Co., we meet Chelsea to feast on gourmet burgers, swap scuba stories, and share life histories. It’s only fitting that our toast to future adventures is made with a tasty sauvignon blanc from a local vineyard whose label just happens to feature—you guessed it—the inimitable leafy seadragon.

Day 21: June 26

Slaves to wind and weather, we’ve been bouncing around Adelaide. Victor Harbor Bluffs is usually good when stiff northerlies prevail. There’s a healthy surface swim—300 yards?—but who cares. Melissa is on fire, finding (all by herself) four leafies along the granite boulders sloping down to 25 feet. The first is a reddish juvenile she spots in just four minutes. The last dragon, at the 90-minute mark, is a bright-yellow adult, super tolerant and a true rock star for the camera. A sea lion makes a brief appearance, but moves too fast for my reflexes.

When the winds are southerly or easterly, Rapid Bay Jetty is the place to be. A long walk (thanks, battle wagon) and a looonnnng swim are required to reach the old jetty’s T-junction, under which fish are packed thick in a shadowy forest of towering pylons. Hundreds of brassy sweepers and strikingly marked old wives—Aussies have a rare gift for naming fish—school in this sublime space, suspended in midwater.

So at peace am I that I never even get around to looking for the dragons that lair hereabouts.

Brandon ColeA diver ventures into a spring-fed site in South Australia's Ewens Ponds Conservation Park.

Day 22: June 27

Our dives at Ewens Ponds Conservation Park outside Mount Gambier are aqua therapy. Three shallow, spring-fed pools wow us with 150-foot visibility and eye-popping aquatic vegetation. Fifty-nine degree freshwater leaking into our suits feels warmish and rejuvenating after three weeks of torture. These limestone sinkholes, only 20 to 40 feet deep, are connected by reed-lined channels through which a gentle current flows, allowing us to coast downstream from pond to pond. Though by no means fishy, there are perch and galaxiid minnows shimmering about, and in the third pool we see the critically endangered Glenelg spiny freshwater crayfish. Scientists call them Euastacus bispinosus. The rest of us manage “pricklybacks.” One reclusive lobster-size lunker is wedged under a ledge, while a shrimpy 4-incher zigzags from algal tuft to tuft. Who would have thought our Oz dive odyssey would include freshwater fun in the middle of farm country?

Day 24: June 29

We’ve come full circle, back to where we started. Weather’s crappy on the Mornington Peninsula, but at this point we’re oblivious to it, basking in the eternal sunshine of our memories of the last few weeks.

Our ebullient mood continues as we drop down Lonsdale Wall from 35 to 90 feet. RedBoats has timed the slack expertly and positioned us on a stellar section of vertical glowing brightly with billions of citrus-hued zoanthid anemones. It’s a perfect backdrop for my portraits of weird and wonderful fish: magpie perch, horseshoe leatherjackets, senator wrasse and longsnout boarfish. Our favorites are the blue devils, sexy damsel-like fish speckled with electric blue.

While gearing up for the last dive—a final farewell to the crabs at Blairgowrie seems fitting—my phone chimes with an email that forever changes our lives. Kade Mills, after careful consultation with his database, confirms that six of the weedy seadragons we photographed at Flinders are new to the Dragon Quest program and will be named in our honor. We have become legend.

NEED TO KNOW FOR DIVING SOUTHERN AUSTRALIA

WHEN TO GO One can dive southern Australia year-round. Those hoping to see both giant cuttlefish and spider crab aggregations will want to aim for the winter months of May and June; May through August is the window for the cuttlefish spectacle. Seadragons and the majority of critters mentioned in this article can be seen year-round. Dragon daddies carry eggs in summer, which generally delivers better weather; January average air temperature is 70 to 75 degrees Fahrenheit. Winter can be cool (average July air temperature is 50 to 55), rainy and blustery.

TRAVEL TIPS Shallow coastal dive sites are very weather-dependent. Winds can wreak havoc with a predetermined, fixed dive itinerary. Be flexible; go with the flow. Rent a vehicle and tanks and move around as the weather dictates, booking Airbnb accommodations as needed. Get a local SIM card with data plan for your phone at the airport upon arrival so you can book accommodations, check weather forecasts, scroll through social media feeds to monitor dive-site reports and connect with the local dive community.

DIVE CONDITIONS Sea temperatures range from about 52 degrees Fahrenheit in winter to about 70 in summer. Bring a 5mm to 7mm full wetsuit, semi-dry or a drysuit depending on seasonality and your thermal tolerance. Many of the jetty dives require long walks and/or swims, so good personal fitness is important. Depths are generally very shallow at the jetties. Deeper wreck, wall and pinnacle dives via boat are possible inside and outside Port Phillip Bay. Visibility at shore sites varies widely, from 15 feet to over 50 feet, depending on wind direction and strength. Offshore visibility often exceeds this. Viz is usually more consistent in winter, except during storms. Current is rarely an issue at inshore sites near jetties but can be strong offshore.

SUGGESTED TRAINING Underwater Naturalist

OPERATORS The Scuba Doctor, Rye: full-service shop and air fills; RedBoats, Portsea: dive charters; Diving Adelaide: full-service shop and air fills; Adelaide Scuba: full-service shop and air fills; Edithburgh Motors: air fills only (+61 8 8852 6067); Whyalla Diving Services: full-service shop and air fills; Adventure Bay Charters: shark diving and sea lion charters

DIVE GUIDES Sam Glenn-Smith; Chelsea Haebich

RESOURCES Marine life ID help: portphillipmarinelife.net.au; Spider Crabs Melbourne Facebook page; Weedy Seadragons Melbourne Facebook page; Dragon Quest program