Divers Reinvent Wreck Diving in the British Virgin Islands with Pirates and Shark-Planeo

Chris Juredin has a most unusual late-night shopping habit.

For many mainlanders, bedtime scrolling leans toward Amazon or perusing real estate listings on Zillow. But the owner of Commercial Dive Services and the recreationally focused We Be Divin’—both based on the British Virgin Island of Tortola—is fixated on boats. Big ones. Big, abandoned wrecks that he and his team of commercial divers can clean up and sink to become habitat, to benefit fish and tourism.

It’s a massive undertaking, but one that he’s had plenty of time to think about.

“I’ve been trying since the early 2000s to encourage the government to let me build artificial reefs,” says the tanned South African wearing a “Black Sheep” ball cap when we meet for coffee.

While Juredin and his reef-centric peers worked on the government, someone with nearly as much money and power as a small country entered the picture.

Local private-island owner Richard Branson—the force behind Virgin Atlantic airline—got involved with BVI’s first artificial reef project in 2017 when a friend persuaded him to help repurpose a boat called the Kodiak Queen, a former U.S. Navy fuel barge that survived Pearl Harbor. (The boat went on to have several lives before 2010’s Hurricane Earl ended its seaworthy days.) Branson and his team of many, including artists and entrepreneurs, helped it be reborn as a wreck off Virgin Gorda.

Kodiak Queen was also Juredin’s first time taking on the dirty, behind-the-scenes work of prepping a ship to become a reef.

“Keeping it afloat and securing it for the artists to work on was difficult. At any time, it could have sunk,” he says. “It would have been cost-prohibitive to resalvage it again. It was stressful. Very stressful.”

In the end, the ship was purpose-sunk without a hitch in April 2017 at a sandy site 57 feet deep.

Juredin walked away with two lessons: one, that he and his team had the skills and equipment to make any vessel perfectly at home underwater. Two, to make this happen, he needed money.

Then Irma hit. Followed by Maria. Two Category 5 hurricanes barreling down on Tortola, Virgin Gorda and Jost Van Dyke within a span of two weeks in September 2017. All talk of reefs and diving halted. All energies poured into recovery. Juredin and his cranes worked around the clock.

When he finally lifted his head, he was in an entirely new position. “All that work from the storm afforded me the opportunity to buy bigger, heavier equipment,” he says.

He was in a place to get things done.

How to Make a Perfect Pirate? Rebarrrr

We approach from the side. Just down a sloping reef sits the Willy T, the legendary floating bar, now resting upright and intact at a depth of 65 feet.

Courtesy Kendyl Berna/Beyond the ReefChris Juredin leaps from the Willy T as the purpose-sunk "wreck" goes down, the last person onboard.

I’m following Megan De Waal, instructor with Blue Water Divers based on Tortola, as she leads us to meet the dead charged with taking care of the ship.

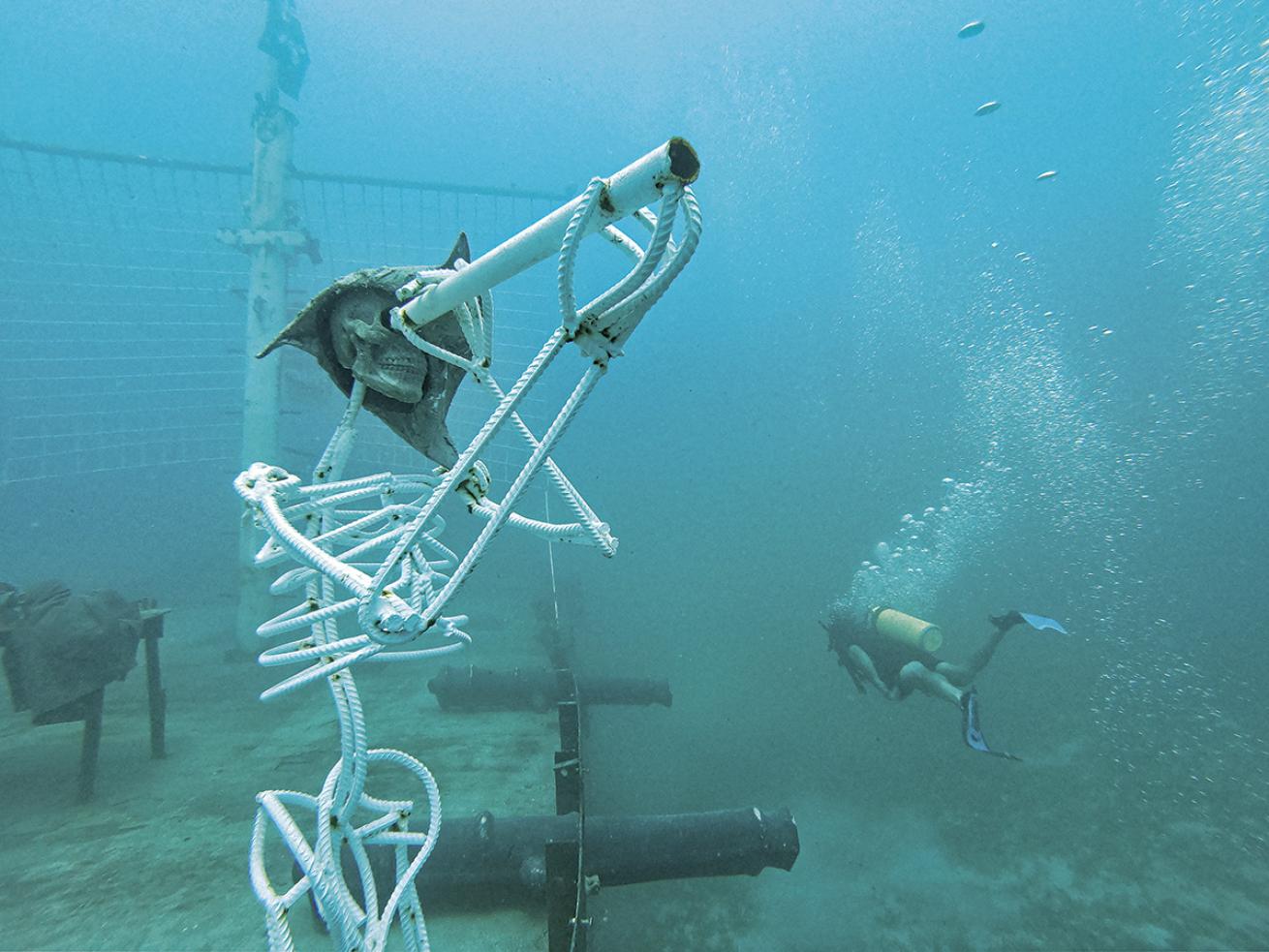

A skull stares back at me, alive with tubeworms and bits of sea fan and sponge. The ship is guarded by a small army of rebar and plaster-of-Paris sculptures, a skeleton crew submerged along with the ship last August.

That was just three and a half months prior to my visit, but it all seems to have been down for much longer. Several rebar pirates sport wire beards, already home to tiny bivalves, shrimp and colonies of critters.

All that growth might have seemed eerie if I hadn’t already learned how it came about a few days earlier at a happy hour for BVI Wreck Week, an annual event that brings metal aficionados to these islands.

There, Kendyl Berna—the other half of nonprofit Beyond the Reef, which Juredin and Berna formed post-Irma—explained why this metal is so conductive, er, conducive, to life.

“Steel is incredibly good for reef building, especially when you weld,” says Berna. “After you weld metal, it holds a charge for a while—and that increases calcification.”

In other words, electrically charged rebar and steel is much like limestone, aiding corals in the process of building colonies. Welded metal can serve as an ideal foundation for growth.

Courtesy Kendyl Berna/Beyond the ReefA pirate skeleton keeps watch over cannons at the stern of the Willy T.

Clearly, a lot of welding took place. It was Juredin and his team who took on all that manual labor. The Willy T is many things, including Juredin’s first success in buying, cleaning, creating artwork for and sinking a wreck with his team, thanks to his new post-Irma paychecks and equipment.

The hours of labor haven’t gone unnoticed by the dive community. Before we splash in, De Waal shares her preferred route, including telling us where all the rebar skeletons are so we don’t miss one.

She also half-jokingly warns us. “Every time I do this briefing, everyone disappears and does their own thing because there’s so much to see on this wreck. I’ve mostly come to terms with this—but please try and stick with me down there, yeah?”

Courtesy Kendyl Berna/Beyond the ReefThe ship's first scuba diving "tourist" was tn the Willy T's deck only about 30 minutes after it was scuttled, greeting by "the captain."

It’s hard not to be distracted. Pirates playing cards. A pirate reading on the porcelain throne. A pirate swabbing the deck. A musket next to a skeleton pirate in the wheelhouse.

It would be easy to devote an entire dive to simply checking out the skeletons. But it’s also fascinating to witness how quickly the sea takes hold. So many shipwrecks began transitioning into reefs long before many of us became scuba-certified. The Willy T is a story we can watch unfold from the beginning.

Encrusting corals, tubeworms and sponges are like the peripheral friends who show up as soon as you buy a beach house—no invitation needed.

As the worms and the corals quickly claim what they can, fish are finding pockets to call home.

Schools of snapper circle the holds. Deeper down, crabs and parrotfish tuck into the small canyon between the ship and the sand, carved by the water’s constant movement.

It’s a living argument—proof that artificial reefs produce impressive results in very little time.

No Stranger to Storms

Irma and Maria worked over most BVI dive sites to some extent, and RMS Rhone is no exception—only, the changes might not be what you would expect.

I stick close to Reka Lukacs, instructor aboard All Star Liveaboard's Cuan Law, the only scuba-and-watersports liveaboard based in the BVI. She’s leading me and a small group of guests to see the bow section of this mail ship, long considered the best wreck in the BVI.

Tanya G. BurnettDestroyed in a 1867 hurricane, BVI's Rhone is one of the Caribbean's most spectacular dives. The wreck offers many dives due to its wide debris field and large, intact structures.

The Rhone is no stranger to hurricanes. Anyone who has dived the BVI has likely heard the 1867 story of Capt. Frederick Woolley’s fateful decision to try to outrun October weather that he believed could not possibly be a hurricane.

But in the tale of Woolley versus the Cat 3 San Narciso storm, we know who won. If you don’t, here’s a spoiler: The bow of the Rhone now sits 85 feet deep.

That depth likely played a role in mostly sparing Rhone from the 13 hurricanes that have barreled over the islands since—including Irma and Maria.

While a handful of shallower sites in these islands were sheared of sea fans and other soft corals, deeper sites were largely out of reach of wave cycles. Because of this, much of Rhone was spared any impact.

As we approach, the foremast and crow’s-nest come into view. The foremast is a rainbow: red tube sponges, orange encrusting corals, purple sea fans. If any life was swept off the site, the two years since have provided enough time for regrowth.

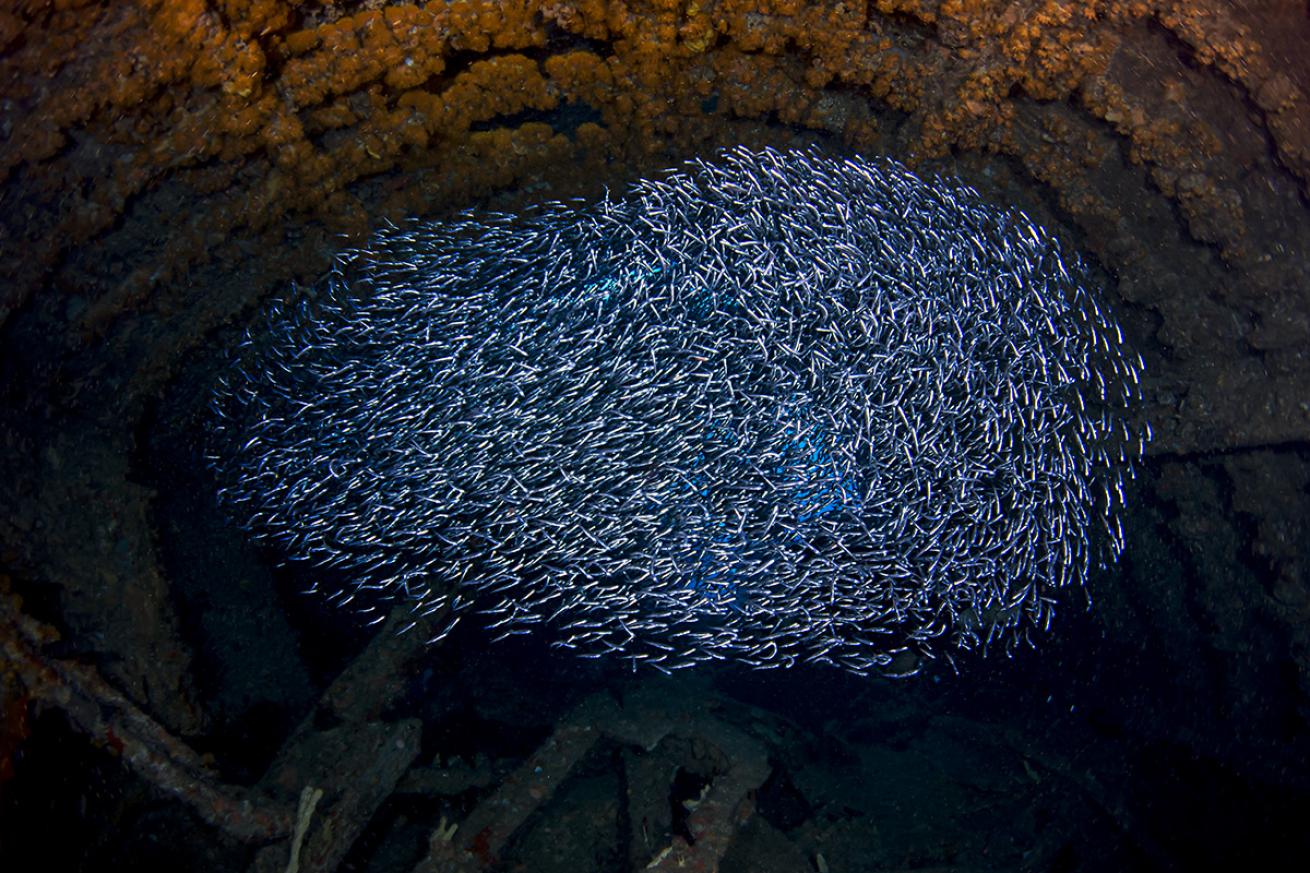

We duck inside the hull, still a cave where massive schools of glassy sweepers dwell. Grunts, angelfish and sergeant majors also crowd inside.

One impact of the storms is that a section of the bow has collapsed just enough that divers now have to swim back out the way they entered, as opposed to swimming through the hull. Otherwise, the dive is every bit the impressive spectacle I remember from past trips. But there is one change.

Out in the blue, one at a time, four Caribbean reef sharks make wide loops around the wreckage before edging in for a closer look at our group.

I’ve dived the BVI every few years since 1994, and never before have I seen sharks here. It’ll be several days before I learn why.

Meet Shark-Planeo

Courtesy Kendyl Berna/Beyond the ReefOne of three "shark-planeo" artificial reefs rests on a sandy plain.

Meanwhile, off the south side of Great Dog Island, one dive site completely vanished post-Irma.

“The first time we were able to come back over here after the storms and have a little look, nobody could find the plane,” says Becca Knight Van Der Werff of Dive BVI. She’s talking about the old Air BVI plane purpose-sunk here in 1993.

Before it was sunk, the wings were removed—the thinking went that the wings could give the plane leverage and cause it to spiral away if a storm ever swept through. That’s precisely what happened, even without its wings.

“Supposedly, there’s a $100 reward if anyone finds it, and they’ll rename it after you.”

No one has laid eyes on the fuselage yet. In its place, the area has become the permanent home of three more planes, creating a new site known as Shark-Planeo. It’s another Beyond the Reef project, born when Juredin and Berna got another wild hair.

Much welding later, those planes were sculpturally transformed into a hammerhead, bull and nurse shark, to bring awareness to species now sometimes seen in the BVI.

They’re shark-planes that divers can swim inside of. Each is meant to be a conversation starter about shark conservation, and also an unbeatable photo op.

We drop down to 40 feet, and there in the sand is the hammerhead. It’s at once amusing and impressive to swim around a metal animal nearly 40 feet long.

Then the glint of teeth catches my eye.

The past few days have seen unseasonable winds from the south, not the typical northeast. The site is silty.

My heart skips a beat, and it’s only as I swim closer that I realize those teeth are tin. Shiny and cut by hand, the work of Juredin and his team. Four rows of pointy chompers appear menacing, balanced by the slight grin of the beast.

Courtesy Kendyl Berna/Beyond the ReefA crane lowers the "hammerhead" Shark-Planeo onto a barge. The new artificial reefs were towed to their new home and sunk onto a sandy plain.

I swim inside the plane, entering from a removed door. In the cockpit, I pose while Van Der Werff snaps a few photos.

We move on to the nurse shark, a bit catlike with its twisty whiskers, and the least threatening of the bunch. We swim on.

Ahead is something I have never seen anywhere else underwater. Local dive operators call it their version of a kelp forest. It’s rows of retired mooring lines, salvaged with all their growth still attached. The sponges are so thick it’s perhaps not surprising that 12 angelfish have settled in between the ropes, weaving among them as we approach.

On our return trip, Van Der Werff takes the time to point out the small things that only a seasoned local guide would see. A juvenile tobaccofish. A sailfin blenny. A colony of 20 skittering hermit crabs, which she tells me back at the surface were all readying to upgrade to bigger shells.

Habitat for All

It’s hard to imagine the full glory of a kraken. Because of Irma, I will never witness the 80-foot metal mesh sculpture as artist Drew Shook intended, but I will see it after the storms took a pass at reworking her shape on top of the Kodiak Queen wreck. I drop in, led again by Dive BVI’s Van Der Werff.

The first thing I notice is the pinkish-white knobby soft corals, like snow blanketing the metal arms of the kraken. I can’t help but think of pygmy seahorses and the soft corals they call home. This would be the perfect habitat for them—if they lived on this side of the globe. But perhaps this artificial reef and its growth will yield discoveries of new species; after all, it’s creating additional habitats that could be conducive to all kinds of life. Time will tell.

Andy DeitschA winter storm "reimagined" Kodiak Queen, leaving a jungle gym for divers.

For now, my eyes follow the outstretched finger Van Der Werff aims at the gunwales. A pair of candy cane shrimp pinch the waters above their heads.

Then my eyes wander a few inches over, and an eye peers back. A tiny octopus, 4 inches high and presumably a juvenile Caribbean reef octopus, winds its arms tighter around itself as it settles deeper into the gunwale. Just a 2-inch-wide pocket, and yet, big enough to house more than a few macro critters.

All told, the wreck offers 1,856 inches—just over 154 feet—of habitat. Jacks form a cloud over the top deck, and a school of grunts darts under and around the kraken arms.

It’s been just two years since the wreck sank, and already it’s quite a fishy environment. Home to far more life than I had expected.

That afternoon, I get to talk fish.

Part of the BVI Wreck Week program is a beach cleanup, with divers, snorkelers and beachcombers collecting trash to help keep reefs clear of debris.

There, I run into Colin Aldridge. He’s the owner of Jost Van Dyke Scuba, and has called that outpost home since the mid-’90s.

Aldridge knows these islands—and he’s noticed a change since Irma and Maria.

After the storms hit, he was cleaning up and rebuilding alongside everyone else. It was months before he could stick his face in the water again.

“When I did, I saw that there’s so much more than there was,” he says, referring to life on the reefs. “I came back, and on one dive, I saw 12 sharks.”

Bulls, Caribbean reef sharks and blacktips are now regular players.

Tanya G. BurnettA silverside bait ball forms up inside the bow superstructure of the wreck of the Rhone.

“Before the storms, it was a one in three chance of seeing sharks. Now it’s 100 percent.”

But sharks don’t show up just because. There has to be a reason.

Aldridge raises his eyebrows. “You know what else was destroyed during the storms? All the fishing boats. Every last one.”

No fishing boats meant fish populations were given a timeout. A chance to rebuild. So while island residents busied themselves with repairing roofs and hauling away wreckage, the fish were allowed free rein to repopulate.

More Fish, More Sharks

Maybe, in the grand scheme of things, hurricanes are part of the natural life cycle for islands—and for reefs. Just as cycles of lightning-sparked fires or droughts can hugely benefit rainforests by allowing them to grow back with a vengeance.

Storms clear out the old. They make space for more life. For the new.

The damage of the storms is not to be underestimated, but the wreckage also speaks to the resiliency of Mother Nature, and of the souls who love her wild handiwork.

This is certainly an exciting time in the BVI, to see fish populations rebound, and to witness record numbers of sharks explore new habitats. Here, underwater, nothing is static. Everything is shifting, adapting and thriving in new ways, creating a reefscape that might not look exactly like it did before— but perhaps that’s a good thing. Nature abhors a vacuum; perhaps these storms created space for more wild things to rush in.

More exciting still, perhaps, is that these are islands to watch. If Juredin has anything to say about it, BVI’s fleet of artificial reefs is about to grow exponentially. You might say it’s an obsession for him. Luckily, it’s one that all divers get to benefit from.

Right now, Juredin has his eye on buying a tanker, and he’s nearly ready to pull the trigger.

It’s only a matter of time.

Divers Guide: BVI

When to go As of press time, BVI was considering reopening to nonresidents no earlier than September 1. For the most up-to-date information, check the official BVI website at bvi.gov.vg and consult your operator.

Dive Conditions Good year-round; trade winds and swell are lighter in summer. Water temps vary from about 78 degrees in winter, when you’ll need a light wetsuit or layers, to 82 in summer, when a skin or bathing suit is fine. Dive sites can experience current, but operators are adept at avoiding it; viz ranges from 40 feet or so, when affected by wind or tides, to 100 on clear days.

BVI Wreck Week 2020 BVI’s next Wreck Week is scheduled for February 14-21, 2021, and is expected to include a pirate beach party at Jost Van Dyke, cocktails at Cooper Island, a beach cleanup on Cane Garden Bay, a Rhone Ball and more.

Operators

- Blue Water Divers, Tortola; Cuan Law liveaboard, docks in Tortola

- Dive BVI, Virgin Gorda and Scrub Island

- Jost Van Dyke Scuba, Jost Van Dyke

Related