How South Africa’s ‘Black Mermaid’ Is Expanding Ocean Inclusivity

Jacki BruniquelZandile Ndhlovu relationship with water changed from fear to freedom on a trip to Bali in 2016. "That trip was the change agent for me," she says.

Zandile Ndhlovu nearly died one of the first times she went swimming.

As a child living in Soweto, a township in Johannesburg, South Africa, she didn’t have direct ocean access. She recalls hearing stories that were meant to deter young people from going into water, such as “there are snakes in the water or white waters that take kids away.” And, although there was a public pool in her neighborhood, it wasn’t free.

“It cost the equivalent of fifty cents per person and my mother never had the (extra) money,” she says. “We had this pristine pool that the larger part of the community didn’t have actual access to.”

In the sixth grade, Ndhlovu almost drowned on a school trip. “We were told to all jump into the water and swim. So even though I couldn’t swim, I jumped in.”

Afterward, she decided to pursue mountain biking. But she eventually returned to water, first swimming at her local gym, then in the ocean.

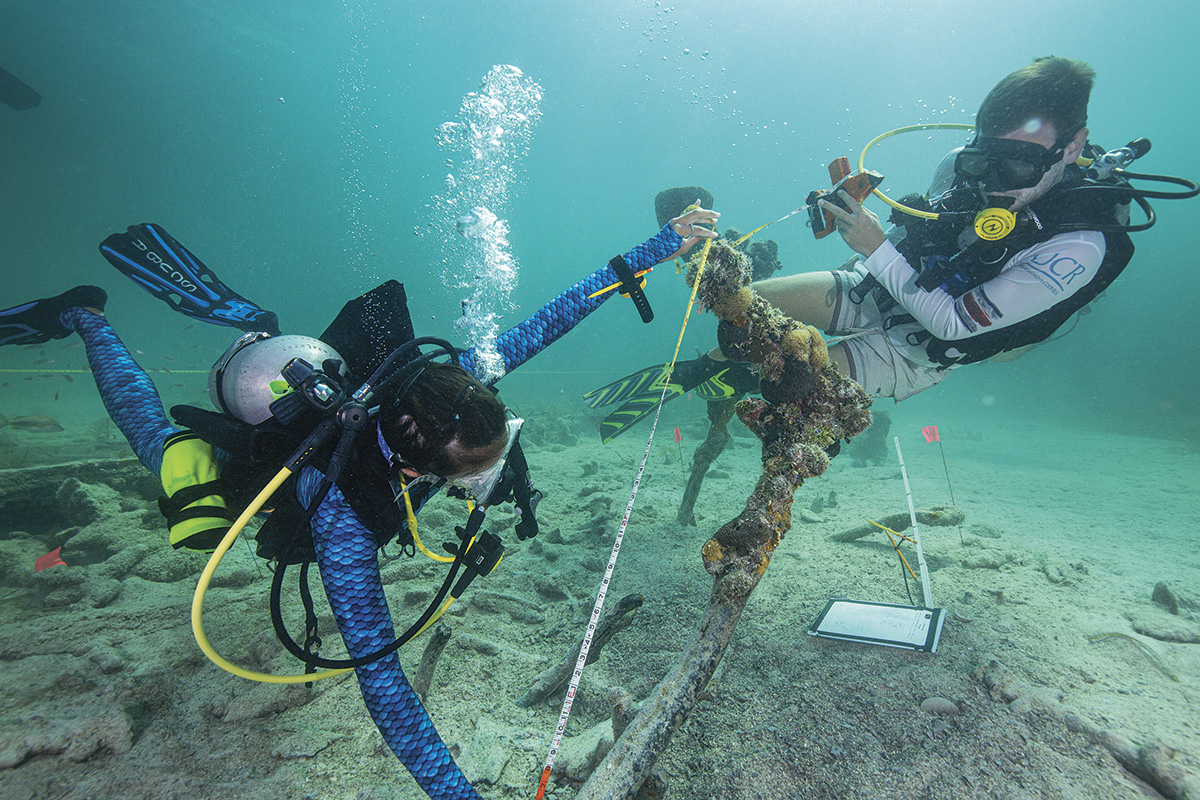

In 2016, she tried snorkeling while visiting Bali. “That trip was the change agent for me,” she says. “It was an incredible experience to realize the amount of life that lives in an ocean. I then knew that I wanted to be in there (the ocean) more, and it became a question of how.”

Ndhlovu went on to earn a free diving certificate in 2017, making her the first Black free diving coach in South Africa. It was just the first step in her ongoing journey to develop other Black divers.

Making Space

The multitude of barriers to ocean access is a major reason there are fewer Black bodies in oceans. During South African apartheid—the institutional method of keeping people of different races apart—Black people were relegated to cramped settlements that were far from the waters the white populations built their houses overlooking and enjoyed in their leisure time.

Although South Africa no longer practices apartheid, the effects are still felt: Low-income Black people still live considerable distances from oceans, making it difficult for them to learn how to swim. And water access is “also about clothing,” says Ndhlovu. “Do we have the correct swim gear? Do we have snorkel gear to be able to see beneath the surface of the ocean, is there a place inclusive enough for Black bodies to exist without fear?”

This is all compounded by inter-generational conflicts around swimming. “If your parents cannot swim, how do they feel comfortable in allowing their child to be in a space that they can’t definitively say is safe?” asks Ndhlovu.

The lack of Black bodies in water led Ndhlovu to set up the Black Mermaid Foundation in 2020.

“On so many of my trips I was the only Black person on the boat and with the foundation, I am helping create the needed access that allows more Black and Brown people to be in the water,” Ndhlovu says. She takes children from disadvantaged backgrounds to the Windmill Beach in Cape Town, where she gives them lessons in swimming and teaches basic snorkeling techniques.

Ndlovu is also trying to help break down common stereotypes around Black people not swimming. “The narratives about Black people around and in water are incomplete. There’s obviously a history attached to it,” she says, referring to the transatlantic slave trade, in which over 12 million Africans were enslaved and transported over oceans for 400 years.

As the first free Black freediving instructor in South Africa, Ndhlovu recognizes her immense privilege—and responsibility. “As a Black body, when you are given any kind of privilege that no one else has, your role is to open it up to the community. You cannot enter the door by yourself. So, I transfer my skills to others like me to make the ocean more accessible.”

In October, Ndhlovu won PADI’s Torchbearer Award, which recognizes PADI Members working to bring balance between humanity and the ocean in their communities.

Her latest foundation project is called ‘Give the Gift of Sight #Underwater.’ “I realized that for people to protect something like an ocean, they have to be able to see it,” she says. “The more people that can receive snorkeling equipment in ocean facing communities expands the idea of people being guardians of the ocean.

Only Getting Started

In addition to her foundation, Ndhlovu is taking on ocean conservation, travel and film-making.

Believing that young people are activists capable of moving the needle on climate change and marine pollution, she regularly visits schools to speak with young people about careers in water-based conservation.

“I tell the kids that when they become leaders, they should create policies taking the oceans into account.” She is encouraged by the presence of African activists at global climate change summits such as COP26.

Jacki Bruniquel"I am helping create the needed access that allows more Black and Brown people to be in the water,” says Ndhlovu of her foundation, The Black Mermaid Foundation.

When she’s not running her foundation, Ndhlovu travels. Her favorite places to free dive in South Africa include Sodwana bay, located in the iSimangaliso Wetland Park and the Kelp Forests of Cape Town. Across the rest of the continent, she cites Egypt as an underrated country for diving. “Diving in Egypt is unique, because instead of the ocean floor, you’re diving to the coral walls.”

Ndhlovu has also ventured into film-making. Her recent short film, 'A World Imagined,' a memoir of her journey to becoming a free diver, won an Aspiring Filmmaker award at the 2021 Banff Mountain film festival, a global festival celebrating adventure, mountains and the great outdoors. Snorkeling with her signature blue braided hair, she describes the oceans she swims in as ‘magical and sacred.’

“I’m excited to tell more stories around the ocean and Black and brown communities and how they relate to oceans,” she says.

8903.png)